As Unions Die, They Become More Popular and More Brittle

Labor union approval reaches new highs as union membership and sector diversity hits new lows.

Interest in labor unions is surging in the United States. During the Biden administration, petitions for union elections at the National Labor Relations Board more than doubled. Biden backed unions in every way he could. Gallup finds that 71 percent of the public now supports unions – a 60-year high.

These trends led many pro-labor folks to hope that the annual Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) survey of American union membership might finally show an uptick. It didn’t happen. The report dropped this week — and despite a progressive National Labor Relations Board and several high-profile union organizing drives, unions continue to shrink.1

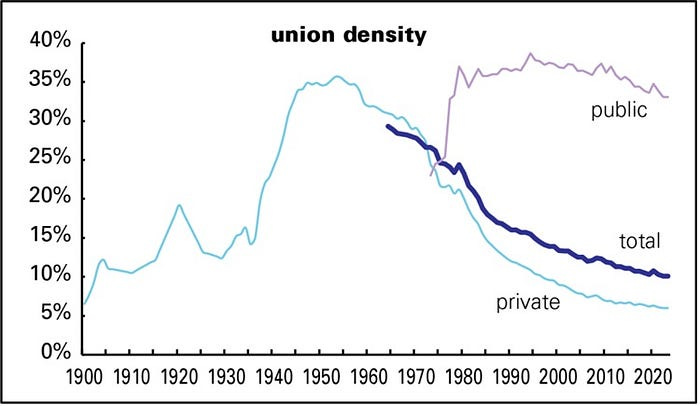

We Have Been Shrinking Our Unions for More than 70 Years

A headline that union membership and density are entering their eighth straight decade of decline is bad enough. But if you dig slightly deeper, the news is even worse: private sector membership is collapsing, but public sector membership is basically stable. 32.2 percent of public employees now belong to unions, compared with only 5.9 percent of private sector workers.

A labor movement (or anything else) that shrinks steadily for seventy years clearly has a problem. However, in the US and most other modern countries, stable public employee unions have masked private-sector union collapse.

Here are the key numbers:

The US has about 161 million workers. Roughly 15.5 million of these are self-employed, so the BLS report covers the 145.5 million Americans who work for an employer.

Of these, 122.7 million work in the private sector, and 21.8 million work in the public sector (e.g., teachers, police, firefighters, and government employees).2

14.3 million workers belong to labor unions, meaning that the share of workers that belong to a union (“density”) fell below ten percent for the first time in over a century.3 In contrast, in 1983, the first year for which comparable BLS data were available, union density was 20.1 percent, and there were 17.7 million union members. The collapse of unions is not the only reason income inequality has worsened since 1983, but it did not help.4

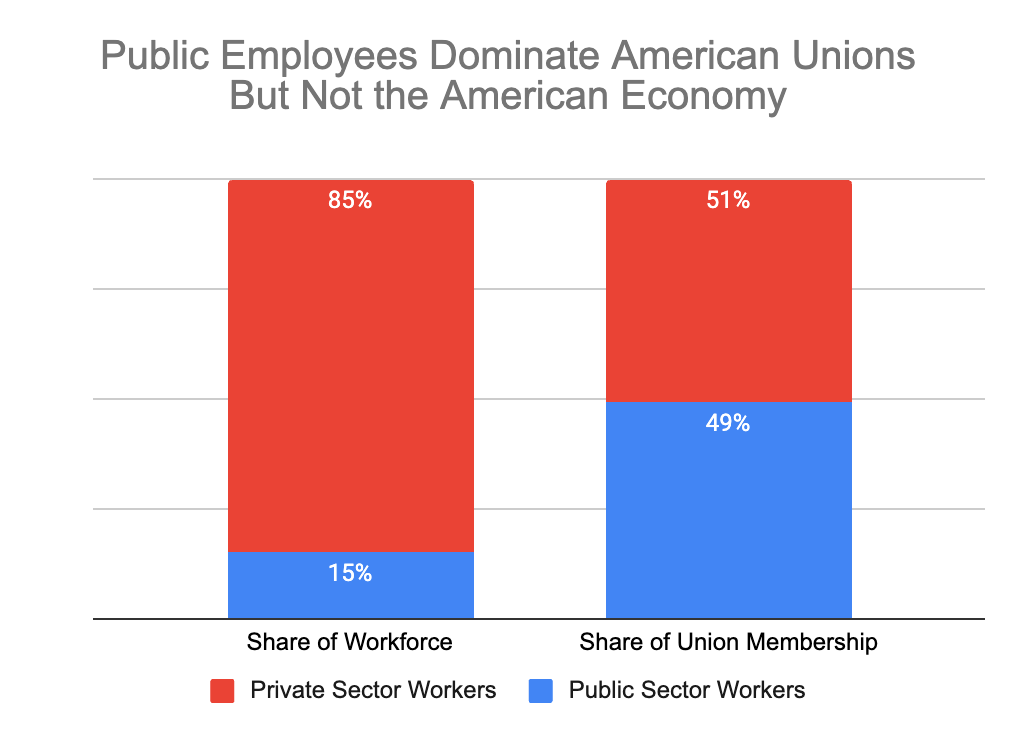

Public Employees Now Dominate Organized Labor

The mask is coming off. The BLS report shows just over 7 million public-sector union members and 7.2 million private-sector members. In other words, public employees, who make up just 14.5 percent of the US workforce, constitute nearly half of all union members. They will soon be a majority.

This is historically unprecedented. When union density peaked in the early 1950s, fewer than ten percent of public employees were represented by unions, compared with a third of private-sector workers. Those proportions have now reversed. Unions represent nearly a third of public workers but fewer than six percent of the private sector.

It is unprecedented historically but not uncommon globally. Public employees make up a larger share of union membership than the overall workforce in every modern country. And union density is shrinking in almost every country, albeit usually from a higher base.5

Public-sector domination weakens the labor movement. Even countries with strong unions have discovered that a labor movement dominated by public-sector workers creates several structural challenges.

Because public employees are more educated and better paid, the labor movement comes to represent higher income workers. This is a massive change. Historically, union members have been less educated than nonunion members. Public-sector jobs such as teachers, social workers, and healthcare professionals often require specialized education. As a result, the median public employee is much more educated and better paid than the median private-sector worker. The BLS indicates that 50-60% of public-sector workers have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 35-40% of private-sector workers. As private-sector unions shrink, the union members in the United States are now considerably more educated than nonunion members.

Raising the pay of the median public employee worsens income inequality. Because public employees are overrepresented in organized labor, American union members are now considerably more educated than nonunion members. This raises a dilemma: reducing income inequality is the primary benefit of labor unions in the minds of many of their advocates, including me. However, you cannot reduce income inequality by raising the pay of above-median workers.

Public sector workers are older, longer-tenured, and more female. A workforce that is better educated, higher paid, more female, and more politically engaged is culturally and politically very different from the workforce in typical low-wage sectors that badly need union representation. Public employees, and especially federal workers, are older and longer-tenured than private sector workers. Because education and health care employ more women and because public employment has historically discriminated less against women, the public workforce in the US is 46% female, compared to only 33% of the private sector workforce.

Public sector unions bargain with taxpayers, not private investors. This makes it harder for teachers, firefighters, or transportation employees to build public support for strikes or protests. Public employee strikes disrupt essential public services in ways that private-sector strikes rarely do.

Public-sector unions depend directly on politically-controlled budgets. As Elon Musk and his team at DOGE are illustrating, public-sector workers are vulnerable to local, state, or federal executives who are hostile to unions and willing to pass laws or issue executive orders that weaken collective bargaining rights.

Public employees are easy to scapegoat. Many in the private sector see them as beneficiaries of stable jobs with generous benefits. This makes it easy to portray their economic demands as excessive or unfair, especially during periods of economic hardship. This undermines solidarity between public and private sector workers and fragments the labor movement.

Public sector unions invariably focus heavily on electoral politics. Because the fate of public sector unions is directly tied to government policies, they prioritize political campaigns, lobbying, and elections. AFSCME pioneer Victor Gotbaum once said the quiet part out loud: “There’s no question about it—we have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.” While this focus can secure favorable legislation, it can divert attention from grassroots organizing or workplace actions. Over-reliance on political strategies also ties union success to election outcomes, which are never predictable.

A labor movement dominated by any single sector is less representative. When unions encompass manufacturing as well as services, high-productivity sectors alongside low-productivity ones, exporters as well as non-tradeable goods or services, they naturally address workers’ broad needs and rights. Without this variety, a labor movement can struggle to address the needs of workers in emerging industries or adapt to shifting economic trends. It becomes more difficult to mobilize support for organizing sectors like retail, distribution, and construction that employ many workers without college degrees — precisely those who benefit most from unionization.

I have argued elsewhere that the solution is to normalize the bargaining of private-sector wages in lower-productivity, non-tradable sectors like health care, retail, construction, hospitality, education, government services, transportation, and distribution. We need to do this without requiring odious organizing campaigns that damage companies and produce unions bent on vengeance. We do not ask owners to fight for their voices to be heard in business decision-making. There is no reason to require workers to do so.

Coda:6

Union density reports come from the Current Population Survey, which queries 60,000 households monthly. This tally excludes self-employed workers. Employment reports like this include the self-employed and show a US workforce of 161 million people.

You can be represented by a union without belonging to one, but in the US, about 90 percent of those represented by a union become members. For simplicity, I focus here on union membership or density, not coverage.

In 1983, the Gini coefficient for income inequality in the United States was approximately .373, compared with .485 today—a substantial increase. (A Gini of 1.0 means that all income goes to one person. A Gini of zero represents perfect income equality. Nordic countries have Ginis in the .25-.30 range.)

Union density has been declining in nearly all countries, including those with historically high unionization rates. Even Nordic countries like Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Iceland, which have strong labor traditions, have seen union density decrease over the past few decades. For example, union density in Sweden peaked in the mid-1990s.

Hat tip for this idea to Paul Krugman. Why doesn’t every Substack have a musical coda?

Public sector unions are directly tied to the Democratic Party. The collapse of private sector unions and domination of the labor movement by public sector unions has created the mistaken view that the Democratic Party is pro-labor, at the same time making it impossible for Republicans to support unions since they fund the opposing party. The Democratic Party was pro-labor under FDR and up to LBJ. Neither party wants to increase private sector unionization (at the risk of offending corporate elites and donors).