II. Subverting Solidarity

Part II of a Labor Day series on how our labor laws weaken private sector unions.

Part One of this Labor Day series summarized the challenges facing private sector unions. It described how the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) has all but destroyed these unions by forcing them to organize. Organizing assumes that a company is nonunion by default. It is expensive and does not scale. Separate from management misconduct, organizing requirements have steadily weakened unions for seven decades.

This post outlines two more features of the NLRA that weaken private sector unions. The law requires that bargaining be both fragmented and exclusive.

This is a paradox. Unions prize solidarity above all other virtues, but NLRA organizing laws require them to tolerate laws that create tiny bargaining units. This fragments collective bargaining and makes solidarity impossible at the exact place it would help the most. Worse, unions insist on monopoly bargaining rights despite evidence that competition strengthens unions. Competition can complement solidarity. It has made for very strong teachers unions. And when unions competed with each other before 1955 they grew at the fastest rate in history.

Fragmented Bargaining Weakens Unions

Employees have concerns that need to be addressed in the workplace, by the company, and for all companies in a sector. Scheduling and work-related issues need to be addressed at work. Policies that govern several workplaces require the attention of senior managers or boards. And wages, training, and skill standards that affect all companies in an industry are best worked out at the sector level.

The NLRA permits none of this. It is set up to enable unions to bargain for a subset of workers within a single workplace of a single company. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) determines which workers share common interests. They have no idea. Most NLRB bargaining units are gerrymanders based on unions or companies trying to win a representation election. This process is bureaucratic and often makes for silly decisions. The NLRB once created a unit of perfume counter sales staff separate from a department store’s other retail employees. Unions tolerate this because tiny bargaining units are far easier to organize.

The NLRB rarely lets unions bargain for all employees in a company like Starbucks that has many locations. They never enable unions to bargain for all workers in a sector. The NLRB manages bargaining rights and cannot provide workers a voice outside of bargaining. The NLRB has no ability to assign labor a seat on a company board. They have no jurisdiction over non contractual consultative arrangements like European works councils.

Bargaining for part of a single company can produce perverse results. A strong union contract can strengthen a company's nonunion competitors. Low-productivity, low-wage industries like agriculture, hospitality, or retail run the highest risk. Sometimes higher wages lead to higher productivity. They can enable a company to attract better workers or invest in technology. But sometimes a union contract leaves a company at a disadvantage to its nonunion rivals. Economists debate how often this actually happens, although it may not matter. Fear of disadvantage shapes management decisions, whether the fear is justified or not.

Not penalizing individual companies is one of the main arguments for setting wages and benefits at the sector level. This offers surprising benefits to companies. When pay is set by sector, employers compete based on improving products, services, or productivity. Many come to see fixed wage levels like contributions to Social Security and Medicare. These payments are set by law and treat every employer equally. Companies don’t love the expense, of course, but they rarely focus on it.

Sector bargaining can enrich labor markets and structure a "race to the top". It can lead to shared training and skill standards that deepen the talent pool. These standards can make it easier for employers to hire and for workers to change jobs. Many companies prefer that labor standards reflect the daily realities of their industry. Legislated standards and regulations designed to be "one-size-fits-all" often don't fit any sector all that well.

Most unions have come to prefer bargaining with part of an enterprise. Even unions that like the idea of sector bargaining imagine it might somehow occur under NLRA rules. But no union can organize a sector. Stronger organizing rights like those contemplated by the PROAct cannot create sector-wide bargaining units. They cannot place labor representatives on boards (which is usually only possible if employees are major owners of a company).

Labor Monopolies Deny Worker Choice and Dampen Union Innovation

Under the NLRA, if workers vote for representation the government grants the union an exclusive bargaining right. No other union has a right to negotiate for workers in that bargaining unit. Exclusive bargaining confines worker voice and reduces worker choice. It has done serious damage to the cause of organized labor.

Congress designed the NLRA for an economy with large companies that bashed metal. As our economy diversified and specialized, it produced an extraordinary variety of workers and workplaces. One union cannot address every worker’s concerns, especially if we enable workers to bargain at the sector level.

Workers vary a lot and so do their preferences. Given a choice, many employees will want to be a part of a large union in their industry. Some may value the training and networking that a professional association offers their occupation. Others may prefer an organization that advocates for women, veterans, parents, libertarians, or Muslims in all sectors. Some workers may simply want to get through their shift and go home. Exclusive representation forces one organization to be all things to all workers. It confuses solidarity with homogeneity and makes for weaker, less coherent unions.

The AFL-CIO reinforces exclusive bargaining by banning its affiliates from competing. Congress permitted unions to do this because they did not want unions prosecuted for price-fixing. (After all, standardizing wages is the entire point of collective bargaining.) But the law permitted federated unions to operate as a cartel -- a serious mistake.

This cartel can easily override worker preferences. When a manager at a large hotel I worked at unjustly fired a co-worker, I asked the Service Employees to help us organize. The AFL-CIO ruled that the choice of union was not up to us. We would need to work with the Hotel Restaurant Workers (now UNITE HERE). This is a solid union today, but at the time it was under FBI investigation for corruption.

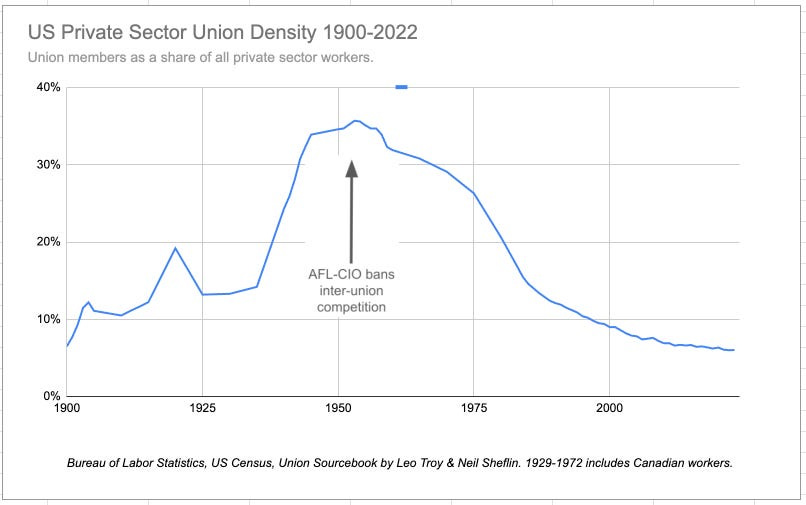

Preventing inter-union competition was the main reason that the AFL merged with the CIO in 1955. Until then, labor organizations competed for members. They fought each other as well as companies. After World War II, union leaders came to view these battles as “raids”, a fratricidal violation of class solidarity.

This was an understandable but profound mistake. Union rivalries were not zero-sum. They forced unions to differentiate and experiment. They produced dynamic and important leaders. Observe what happened to organized labor’s market share when unions stopped competing.

School teachers took a different route and their unions thrived. Two unions competed to represent teachers: the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA, which never joined the AFL-CIO). The two organizations fought frequently and hard. The fights were often expensive, but competition forced both unions to replace ineffective local leaders and to absorb weak locals into stronger ones. Both developed impressive grassroots political operations and reputations for highly engaged members. Both grew strong in Right-to-Work states. Today, for better and occasionally for worse, 70% of public school teachers belong to unions. The NEA is America’s largest labor organization. There is little doubt that decades of competition helped to produce two of America’s strongest unions. Nonetheless, many union leaders struggle to appreciate how competition and choice complement solidarity.

Cartels usually fall apart because the rewards for defecting are too high. AFL-CIO attempts to prohibit competition may be no exception. The three largest unions in the country are not part of the AFL-CIO. The NEA never affiliated. The Teamsters were kicked out before rejoining and then quitting. The Service Employees and other unions left in protest. Many former members of the AFL-CIO are now experimenting with novel approaches to recruiting and representing workers. Sometimes this means competing with other unions or ignoring traditional jurisdictional arrangements. The Fight for $15, Justice for Janitors, and the wage board campaign for home health care workers in California are some of the largest innovations in labor organizing since Cesar Chavez pioneered community boycotts to pressure grape growers in the 1960s.

Competition and choice animate markets and democracies; nothing else does. Many factors contributed to the rapid growth of unions when they competed. The AFL-CIO ban on competition was not the only cause of union decline, but it is hard to argue that exclusive bargaining or AFL-CIO restrictions on competition helped unions grow or innovate.

Exclusive bargaining has a subtle and pernicious economic impact on unions. It imposes on unions a "duty of fair representation". This duty obligates a union to represent every member of a bargaining unit, whether they join the union or not. In response, unions bargain security agreements that require workers to contribute dues or fees. This practice becomes controversial mainly when anti-union forces advocate for state right-to-work laws. These laws ban union security agreements.

Unions depend on dues revenue associated with exclusive bargaining. If workers were free to join any union they pleased (or none at all), unions would have to either recruit more widely or develop new revenue models. This is tough for a union to do if NLRB organizing rules prevent it from growing, reinforce fragmented bargaining, and award only exclusive bargaining rights.

In Part III of this series, I will outline an approach to bargaining that would enable unions to grow again by recruiting, not organizing. It would provide for worker voice at the workplace, board, and sector level. Workers would have a broad choice of unions or professional associations. This approach would create a strong incentive for companies to organize and for unions to form bargaining coalitions. Like any new approach, it has risks, including the risk of unintended consequences. And it needs to be able to attract a winning political coalition.

Note: Oren Cass at American Compass, a pro-labor conservative think tank, has published a condensed version of this series here.

If the third installment is as good as the first two, I hope you figure out a way to get the entire piece published as broadly as possible. The writing is excellent, and the insights are exceptional. I appreciate how you utilize supporting data, as well as your own personal experiences.