Will Democrats Decide to Win?

Beating MAGA Requires Smarter Economic Populism

“Winning an election is a decision. You make a decision to win, and then you make every decision in favor of winning.” — Nancy Pelosi.

Politics is about power — not about self-expression, analysis, or pet projects. Political parties exist to build coalitions that can win power and use it for the common good.

The founders called parties “factions”, which they so distrusted that they excluded any mention of them from the Constitution. To contain factions, they preferred to balance power among the three branches. Today, the balance of political power within each branch arguably matters more than the Madisonian checks and balances that so fascinated those who drafted the Constitution.

“I Belong to No Organized Political Party”

Modern parties are as much networks of ideas as organizations. They’re loose collections of donors, issue groups, pundits, staffers, and elected officials. In DC, the saying is that “When you call the Democratic party, no one answers the phone”. Or, as Will Rogers once joked, “I belong to no organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

Party coalitions necessarily include both left-wing standard-bearers like Zohran Mamdani, Bernie Sanders, and AOC, as well as more moderate or conservative Democrats. Not long ago, Democrats from red states like Kansas, Missouri, and Ohio were pro-life. When Obamacare passed, the House included roughly forty pro-life Democrats. Today, there’s one: the scandal-ridden Henry Cuellar of Texas (just pardoned by Trump).

Donald Trump understands coalition-building better than many Democrats. He’s delighted that Susan Collins won Maine, a state he lost to Kamala Harris. He doesn’t publicly attack her pro-choice politics. He welcomed RFK Jr. and his Joe Rogan–adjacent voters into the Republican fold because they helped him win.

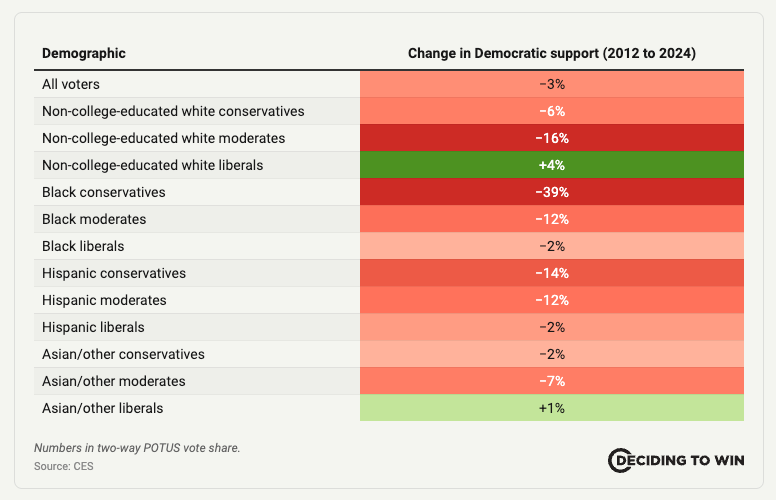

A party runs on an infrastructure of highly educated staffers, donors, advocacy groups, and politicians. When these people adopt new priorities, the party’s brand changes. Since 2012, as professional Democratic elites have shifted focus, they’ve drifted from the bread-and-butter concerns of the largely non-coastal, non-college-educated electorate. As the party drifted, it lost credibility with vast swaths of voters.

Of course, issues like abortion, climate, and social justice matter to many committed Democrats. But when they eclipse affordability, jobs, crime, and immigration, many voters feel ignored. That suppresses turnout among sympathetic voters and bleeds support among moderates and working-class people who feel their concerns are being sidelined. The result is a credibility crisis.

The Last Time This Happened

Democrats have been here before. In September 1989, the party was in the dumps. Ronald Reagan had just completed two terms. His bland vice president, George H. W. Bush, not only won a third straight GOP term; he crushed Michael Dukakis 426–111 in the Electoral College and became the first sitting vice president to win the presidency since Martin Van Buren in 1836. Democrats were despondent.

That month, Elaine Kamarck and William Galston published The Politics of Evasion: Democrats and the Presidency. It pulled no punches:

Without a charismatic president to blame for their ills, Democrats must now come face to face with reality: too many Americans have come to see the party as inattentive to their economic interests, indifferent if not hostile to their moral sentiments, and ineffective in defense of their national security.

… Instead of facing reality, they have embraced the politics of evasion. … In place of reality, they have offered wishful thinking; in place of analysis, myth.

They warned Democrats could either “hunker down, change nothing, and wait for some catastrophe … to deliver victory,” or confront their weaknesses by nominating a candidate who was:

fully credible as commander-in-chief

aligned with the moral sentiments of average Americans

offering a progressive economic message rooted in upward mobility and individual effort

and willing to recast the party’s commitments in ways that could build a durable majority.

A 43-year-old governor of Arkansas read the report and took it seriously. Bill Clinton worked closely with Kamarck and Galston, used their analysis to reshape the party, and won the presidency in 1992.

Deciding to Win

Democrats face a similar moment now. Right on schedule, a new report inspired by The Politics of Evasion has arrived.

Simon Bazelon and the political action committee called Welcome have produced a 60-page report, Deciding to Win, that is just as cold-blooded.1 Its central alarm bell: 70% of voters think the Democratic party is “out of touch.” For anyone who cares about implementing progressive policy or simply stopping MAGA, that’s a five-alarm fire.

The report shows how, over the past dozen years, Democrats have drifted left on climate and culture and away from the economic concerns that remain voters’ top priorities. To reclaim majorities, Democrats must reorient around economic populism and real-world anxieties: inflation, cost of living, jobs, public safety, and border security.

That’s not a cosmetic tweak. It’s a rethink of what “winning” looks like in 2020s America.

The report picks 2012 as the inflection point. Barack Obama’s reelection coalition blended middle- and working-class voters, suburban moderates, and liberal urbanites around a broad economic message. Since then, the share of Democratic members of Congress cosponsoring progressive legislation has climbed sharply.

Democrats began talking less about the cost of living, jobs, crime, and immigration, and more about climate, identity, and culture. Deciding to Win describes a severe “Democratic penalty” — a structural disadvantage attached to the party’s name. By 2025, 54% of voters thought Democrats were too liberal — a larger share than thought Republicans were too conservative.

The brand damage is quantifiable. In head-to-head tests, Democratic candidates underperformed their independent counterparts by more than 8 points when delivering the exact same economic populist message.

Let that sink in: the perfect kitchen-table economic message is roughly eight points less effective when it comes from a candidate with a “(D)” next to their name.

The penalty is worse among the former backbone of the party: working-class, Latino, rural, and swing voters. In key states like Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, the Democratic brand penalty swells to 11–16 points. No party can consistently win national elections — especially given the tilt of the Senate and Electoral College — while repelling double-digit shares of the swing electorate.

Most Voters Are Not Politically Liberal

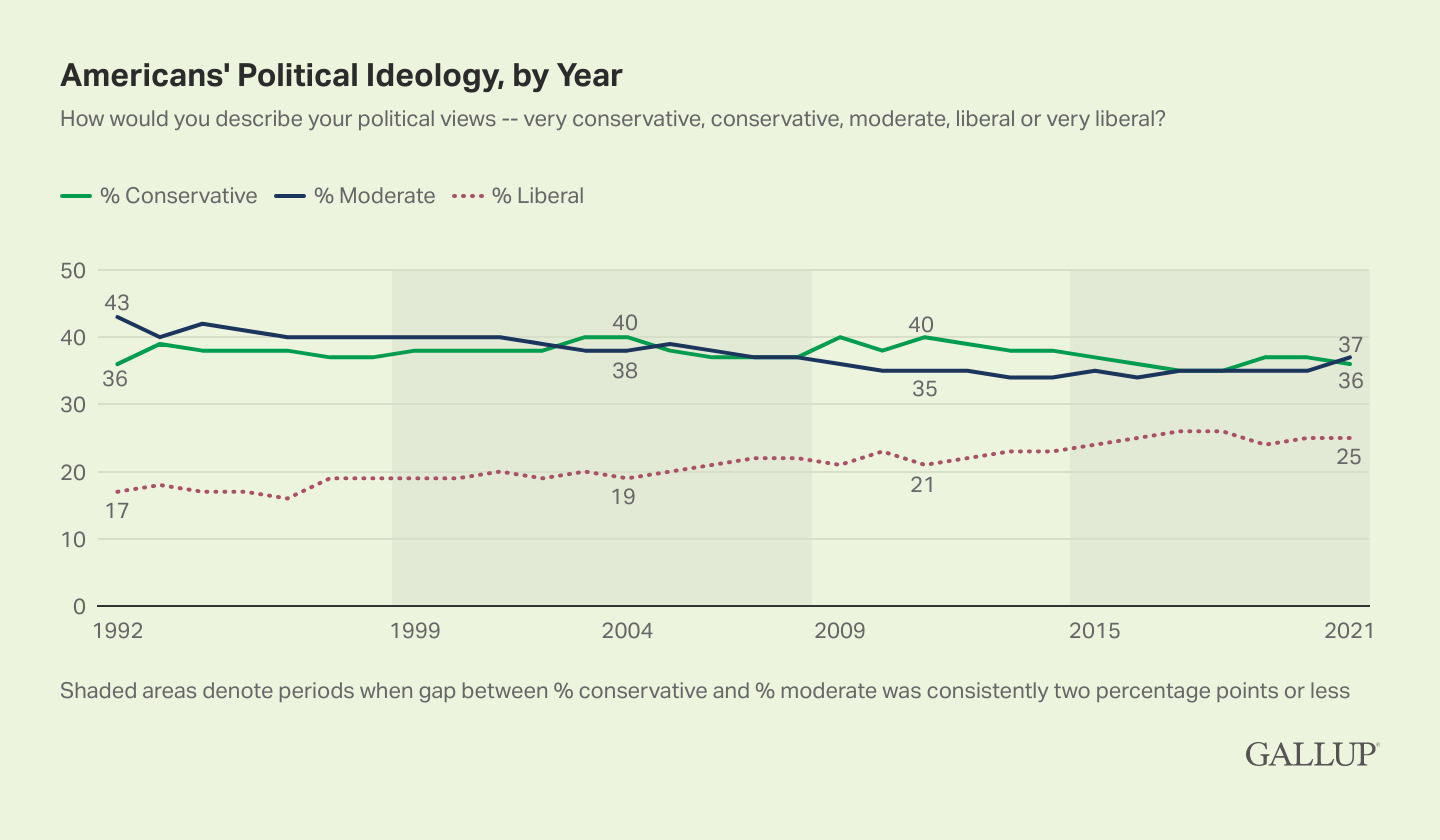

At the heart of Deciding to Win is a simple claim: most voters identify as moderate or conservative, not liberal. Gallup polling over many decades is unequivocal: about 71% of Americans call themselves moderate or conservative.

These voters prioritize cost of living, healthcare, jobs, border security, and public safety over the cultural and political interests of highly educated and affluent voters who dominate the party’s internal conversation. Many voters have concluded Democrats care about something other than their central concerns.

One post-election poll found that while 47% of voters listed the economy among their top three concerns, only 17% thought the economy was among the issues Democrats cared about most. That gap is stark — and lethal.

The authors argue a winning Democratic strategy should re-center on an economic agenda: improving affordability, lifting wages, expanding the safety net, making the wealthy pay fair taxes, controlling drug prices, and raising the minimum wage.

Even crude measures show the drift. A word-frequency analysis of the party’s 2012 and 2024 platforms — the latter opening with a four-paragraph land acknowledgment for Chicago — illustrates how cultural messaging has crowded out economic language.2

The Myth of Mobilization

Deciding to Win demolishes what it calls the “Myth of Mobilization.” Many progressives argue that Democrats should lurch left to “fire up the base” and boost turnout. The data say otherwise.

Moderates consistently outperform progressives.

Swing voters decide close races.

Sporadic Democratic voters are more centrist than the die-hard base.

Winning requires persuasion and turnout — both driven by a clear focus on cost-of-living and kitchen-table issues that resonate with swing voters and sporadic voters alike. Simply increasing turnout, without changing who you appeal to, risks adding as many votes for Trump as for Democrats.

What Worked in 2024

The report mines recent elections for concrete lessons. Many successful Democratic congressional candidates in 2024 ran ads emphasizing crime, immigration, and public safety — the very issues coastal progressives often treat as politically toxic for Democrats.

That’s what it means to “meet voters where they are,” instead of where donors or activists wish they were. It’s not about abandoning liberal values. It’s tactical humility: recognizing that voters may support progressive economic policy while still wanting safe neighborhoods, secure borders, and relief from inflation.

When it comes to winning, tone, empathy, and message discipline matter as much as policy.

“Moderate” is often treated as a synonym for lukewarm or timid. Deciding to Win — and history — tells a different story. Being moderate in this sense means aligning with the lived reality of working-class families, suburban parents, small-town voters, and young people facing rising rents. It means building a coalition around widely shared beliefs and moderating stances on hot-button issues — immigration, crime, identity, energy — not by abandoning values, but by recognizing where public opinion actually is.

Deciding to Win does not counsel weakness. Democrats should still advance core values, protect disadvantaged groups, and stand firm against Trump and the GOP’s extremism. But they should be disciplined and strategic in which fights they pick, and how, concentrating on issues where they have broad public backing: protecting Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, opposing tax cuts for the wealthy, and resisting Trump’s tariffs.

The candidates the authors praise — Ruben Gallego, Marie Gluesenkamp Pérez, Mary Peltola, Jared Golden, Tom Suozzi, Marcy Kaptur, Vicente Gonzalez — share a basic posture: they reject both neoliberal triangulation and progressive purity. Their message is simple: We know what’s stressing you out — groceries, rent, inflation, safety — and we’ll act. Often, that has worked.

Headwinds and Opportunity

The problem is not just messaging. Deciding to Win documents the structural disadvantages facing Democrats.

Democratic Senate candidates often face electorates to the right of the national median. As a result, winning the national popular vote is not enough to win the Senate. Ticket-splitting is rarer than ever, so House and Senate races move in lockstep with the top of the ticket. National reputational damage flows down ballot.

How bad is it? Not only are voters eight points less likely to vote for a Democrat than an independent who takes identical positions, but the Senate map tilts roughly three points rightward. When 580,000 people in Wyoming elect the same two senators as 40 million people in California, the challenge is obvious.

Yet the same structural forces that now punish Democrats for being seen as too liberal also create opportunity. Republicans have governed in ways that have pushed up costs, disrupted supply chains, strained alliances, and undermined faith in institutions. Economic anxiety is real.

That means there is a receptive audience — especially among working-class voters, suburban families, and culturally moderate but economically insecure voters — for a renewed Democratic message centered on economic justice, stability, and concrete solutions.

The Decision

The title Deciding to Win is deliberate. Nancy Pelosi’s mantra — making “every decision in favor of winning” — captures what’s required: resisting ideological purity tests, donor-driven pet issues, and the fantasy that identity or cultural signaling alone can hold a coalition together.

In practice, that means:

Prioritizing an economic agenda: cost of living, wages, health care costs, taxes, public safety, and border security.

Modulating tone and emphasis on culturally charged issues that are not top voter priorities.

Recruiting and supporting candidates who genuinely share working-class concerns and frustrations, rather than triangulating from above.

Rejecting both corporate-centered neoliberalism and left purity politics in favor of a big-tent coalition built around shared economic concerns and common sense.

One of the report’s sharper observations is that what used to be called “common sense” — economics-first, voter-oriented politics — has become unfashionable inside much of the party. Internal incentives reward ideological signaling over mass appeal: donors applaud sweeping climate promises, pundits praise culture-war stands, and activists organize around identity. Those stances gratify parts of the base — but alienate millions who Democrats need to reach.

Shifting back to common sense requires not just a strategic reset but a cultural one. It means breaking the echo chambers of D.C., Brooklyn, and Oakland and engaging with working-class small-town voters, suburban parents, small business owners, grocery clerks, factory workers, and renters.

That’s intellectually messy. But if Democrats want to defeat Trumpism rather than simply posture against it, it’s necessary.

Discipline, Clarity, Courage

Recent polls and elections suggest that Trump’s manifest incompetence will tempt Democrats to rely on a backlash in the 2026 midterms. And if this works, there is no reason for Democrats not to take advantage of it.

A recent Fox News poll reflected widespread economic dissatisfaction and a preference for Democratic approaches to affordability. A substantial majority of voters (76%) described current economic conditions as either “only fair” or “poor”. A plurality (46%) felt that Trump’s economic policies had harmed them — a higher negative perception than was ever recorded for President Biden’s policies in previous Fox News polls. Most voters (62%) held Trump responsible for the current state of the economy, compared to just 32% who had blamed Biden. Most (52%) felt that inflation is “not at all” under control and reported that their costs for groceries (85%), utilities (78%), healthcare (67%), housing (66%), and gas (54%) had increased over the past year. Significantly, 53% of respondents believed Democrats have a better plan to make things more affordable than Republicans (43%).

As more Americans connect Trump’s tariffs to higher prices, see his neglect of housing and energy costs, register their anxiety about crime even in cities where rates are falling, and watch him mismanage immigration, Democrats have a chance to rebrand. Those windows don’t open often.

If the party internalizes Deciding to Win, the next two years could be a hinge. As in the early 1990s, Democrats could start to reassemble a coalition of working-class voters, moderates, and upwardly mobile small-town families — updated for the 2020s.

That would mean fighting for good policy, especially policies that don’t come wrapped in purist progressive rhetoric. It would mean the discipline and clarity to choose battles that matter most to voters. Above all, it would mean a decision to win, not just to signal virtue.

If Democrats refuse this path, they risk becoming what the report calls “a party of high-propensity voters” — dependent on low-turnout specials and midterms, increasingly disconnected from the majority of Americans. They could win the House in 2026 but would become a long-term minority party in the Senate and forfeit any chance to reshape the American judiciary.

If, however, they decide to refocus on what voters care most about and adapt to the changed electorate, Democrats might reclaim a governing majority.

Economic populism and common-sense moderation won’t solve all of America’s problems, especially in an era where high-income Democrats back redistribution and non-college Republicans support tax cuts for the rich. But Deciding to Win does something rare: it looks to data, not ideology or donors’ wish lists, to focus on voters’ stated priorities.

If you care about actual policy outcomes — affordable living, stable jobs, safe communities, real opportunity — you should read the report. It isn’t cynicism. It’s realism.

Will realism prevail? Will Democrats decide to win? If they don’t, they won’t.

CODA

Bazelon is the son of the New York Times legal affairs journalist, author, and podcast host Emily Bazelon.

The 2024 platform opens with a four-paragraph apology for convening its convention in Chicago on former tribal lands. As Matt Yglesias recently noted, “…if we want to defend the ideas of liberalism, pluralism, democracy, and all the rest, we can’t accept the premise that there’s something uniquely criminal about the origins of the American state.”