Will AI Improve Social Trust?

With leadership and transparency, it might. But don't bet on it.

While cycling through the Danish countryside several years ago, my wife and I came upon a farm stand selling cherries and plums. There was no vendor and no prices, just baskets of fresh fruit and a jar with a request in English to “pay by your ♥️”. I complied, snapped the photo, and was impressed at how much cash was in the jar unprotected. The farm appeared to be prospering without the need for clerks or surveillance to enforce basic honesty.

Denmark is often regarded as a high-trust society, partly because it is a small and relatively homogeneous country. However, farm stands like these can also be found in rural America.

Economist Kenneth Arrow once wrote that “Virtually every commercial transaction has within itself an element of trust ... It can be plausibly argued that much of the economic backwardness in the world can be explained by the lack of mutual confidence.”1

Arrow understood that although trust and integrity are difficult to measure, they are essential to economic life. He realized that trust reduces transaction costs and limits the need for enforcement, surveillance, courts, cops, and attorneys. He believed that high-trust environments were more efficient, adaptable, and innovative.

In Power and Prosperity, the economist Mancur Olson argued that trust in institutions enables long-term investment and complex coordination. IMF data suggests that he was correct, finding that high-trust countries invest more, trade more, and innovate more. Citizens of high-trust countries are more likely to comply with laws and regulations, in part because they trust government institutions. Individuals in high-trust societies tend to report higher levels of life satisfaction, happiness, and social well-being.

Trust and integrity are invisible to GDP statistics and economic models but instantly visible to everyone else. You cannot miss the difference when visiting high-trust countries like Denmark or Japan. Or low-trust countries like Brazil.

Trust and integrity shape culture

It can be hard to distinguish cause from effect when studying social trust. Countries with robust social security systems, affordable healthcare, and high-quality education tend to have higher levels of trust. More transparent governments build trust, as do strong legal systems that consistently enforce laws and minimize corruption. Researchers debate whether high social trust helps to produce these systems or whether these systems foster high social trust. Or is it a virtuous cycle with a feedback loop that is hard to start but, once established, creates a positive-sum culture that can become self-reinforcing?

The need for trust is evident everywhere in culture; it is not confined to the economy or the provision of public services. High trust emerges more often in institutions and societies that can acknowledge mistakes and are led by people with the discipline to avoid shortcuts, especially those that could result in personal gain.

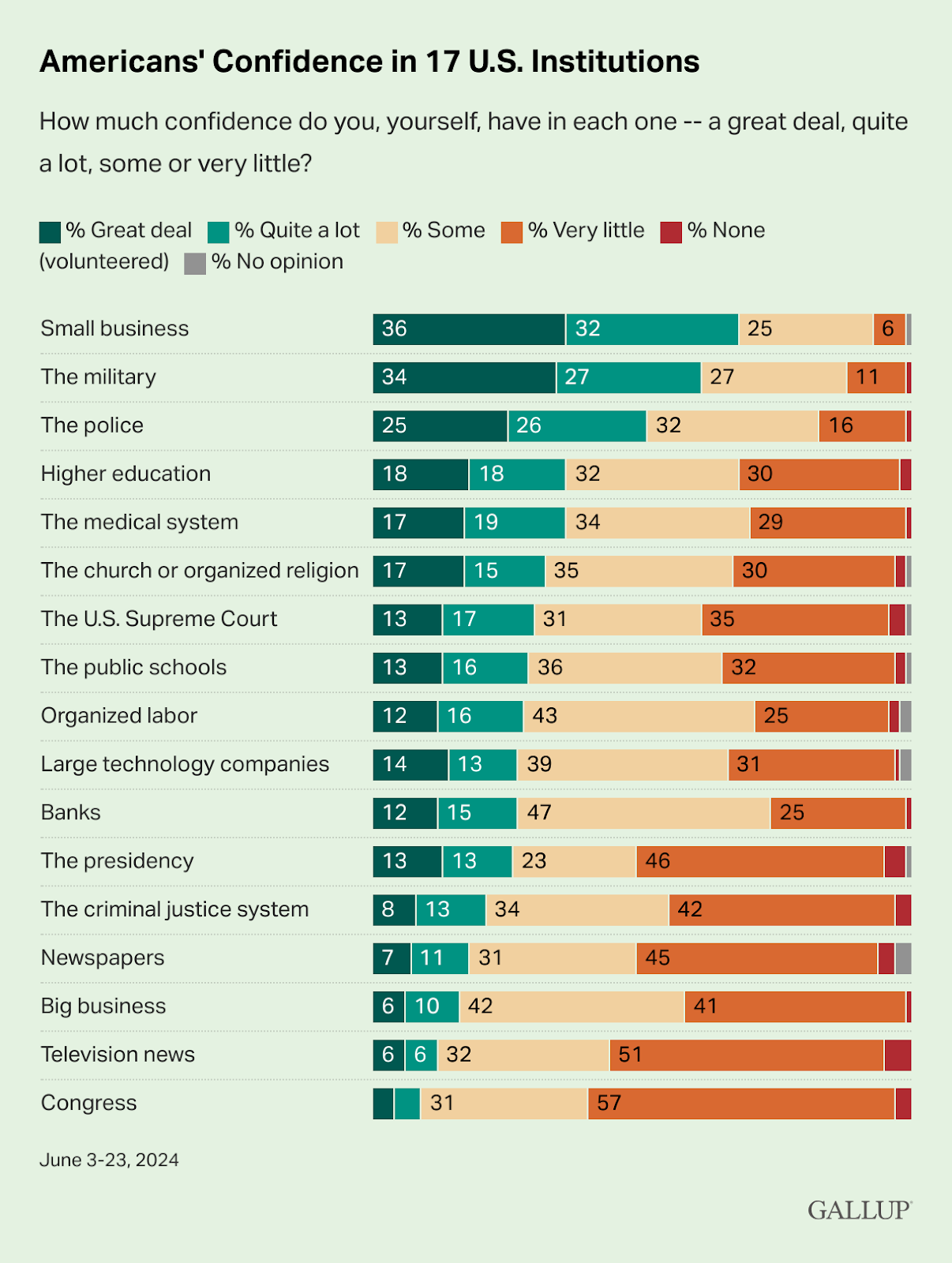

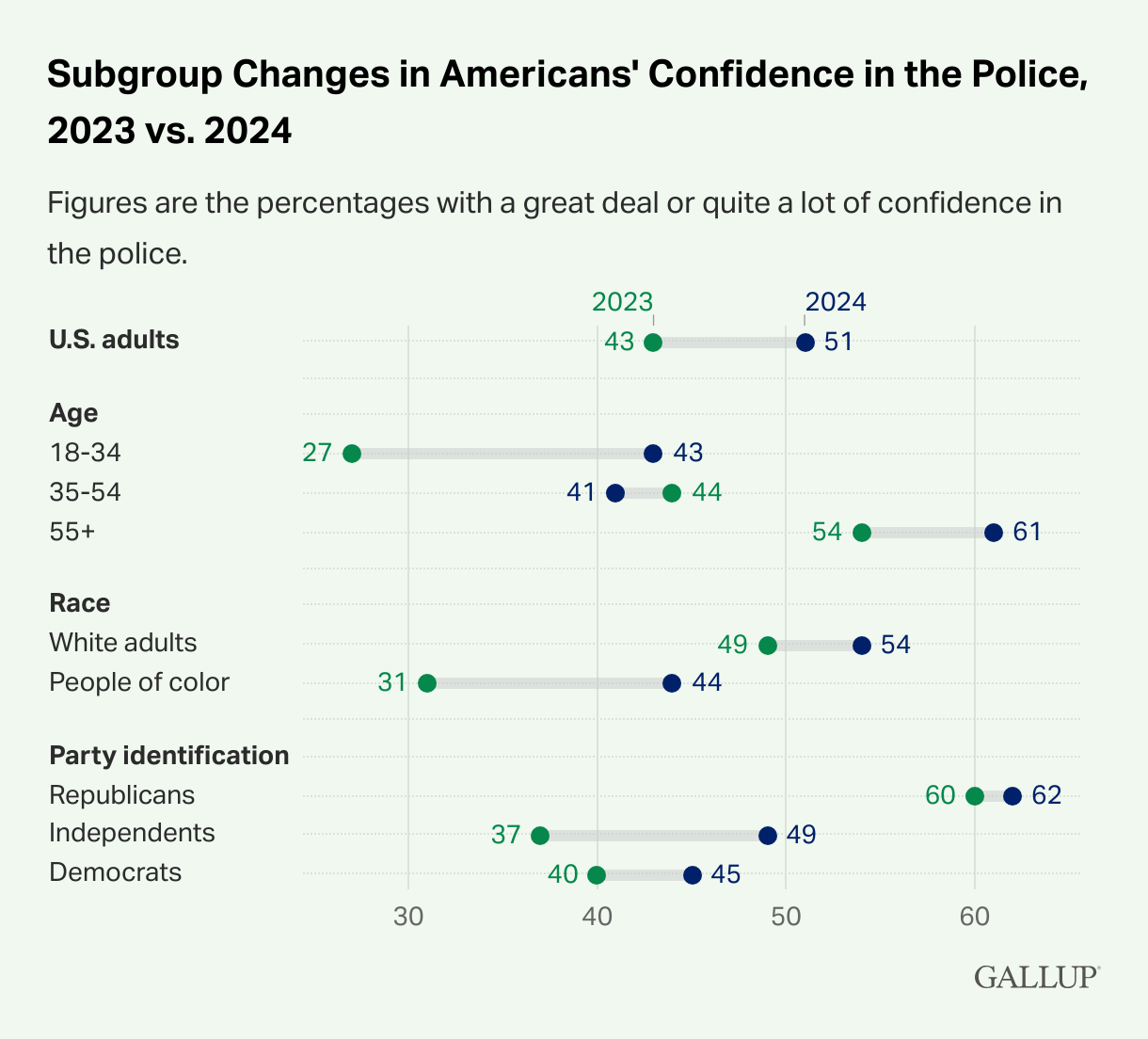

Gallup finds that Americans’ trust in major U.S. institutions is at a historic low. Only small businesses, the military, and the police are trusted by a majority of the population.2

It is worthwhile to examine how trust operates within specific institutions.

Academia. Integrity in scholarly research means more than avoiding lies. It means maintaining a culture where rigor, transparency, and long-term contribution matter more than careerist publishing metrics. When we measure publication counts and impact factor to gauge research output, we tempt scholars to manipulate these metrics. By rewarding quantity over quality, we encourage intelligent people to produce knowledge that has little to no value. We create incentives for P-hacking, sloppy methods, and outright fraud. The result is the replication crisis that has eroded the credibility of the social sciences.

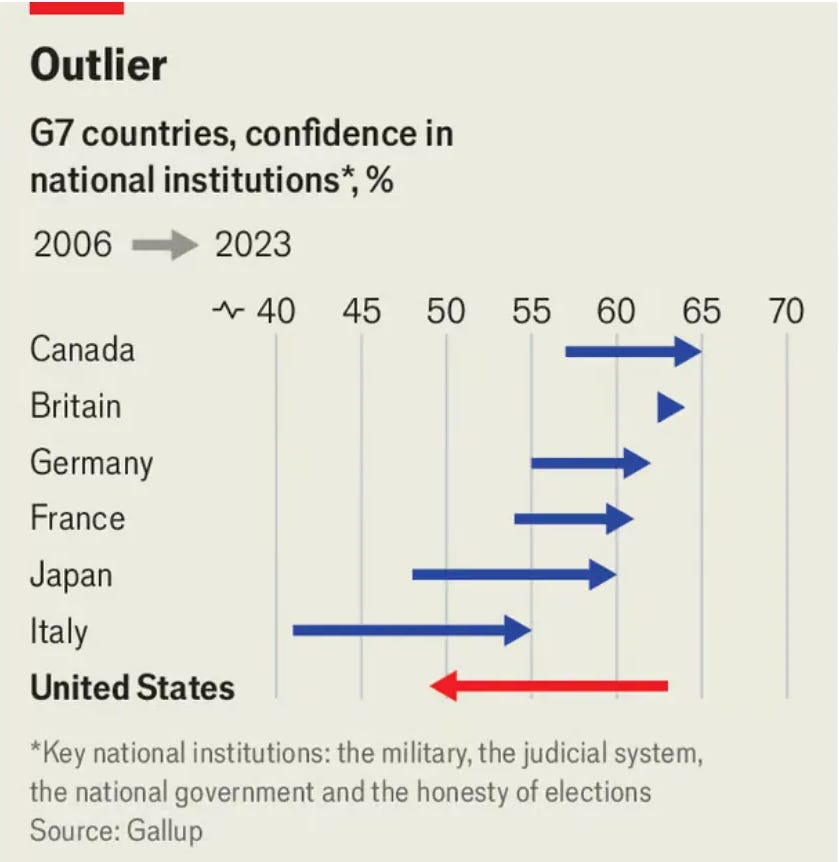

Politics. Gallup finds that political trust and integrity have eroded much more sharply in the United States than in most other countries. Sixty-five years ago today, the Soviet Union shot down an American spy plane, and US President Dwight Eisenhower denied knowing anything about it. When it emerged that he had specifically authorized the flight, the American people were outraged that a president would ever lie to them, even over a highly classified national security matter. When Nixon lied about Watergate, the country was so shocked that bipartisan pressure forced him to resign, even though he had won 49 states.

Today, when a cabinet nominee lies to Congress, there is barely a ripple. A president who lies daily and sows distrust of neighbors and allies produces indifferent shrugs. As public expectations fall, the integrity threshold for public office plummets. The long-term result isn’t just cynicism, it’s institutional dysfunction. Policies become more erratic, more performative, and less credible. Policymaking degrades into theater.

Media. We still have excellent journalists and trustworthy outlets, but they must now compete with algorithmically amplified propaganda. Conspiracy theories and outrage bait reach millions of people daily, not because they’re credible, but because they’re profitable. Worse, we immunize from liability any platform that amplifies addictive bullshit to sell advertising. Not surprisingly, trust in the media has collapsed.

When the public loses trust in journalism, it loses one of its most essential checks on political corruption. This creates another feedback loop: low trust enables corruption, which in turn further erodes trust. As that loop tightens, democratic accountability diminishes.

Business. The same is true in business. In low-trust societies, entrepreneurs allocate more resources to compliance, security, and navigating gray markets. Investment slows and talent flees. High-trust societies don’t just work better; they attract better people and better ideas.

McKinsey & Co. is a cautionary tale. When I worked there during the early nineties, the Firm terminated low-integrity clients and consultants. A colleague who told a partner that he had made a phone call when he had not was shown the door that day. We stopped serving a client when we discovered that they misrepresented material facts in their public statements. It was a demanding but exceedingly high-trust professional environment. Based on a series of scandals during the past decade, this appears to no longer be the case.3

Organized labor. For good reason, labor unions are often perceived as reactive, zero-sum, and low-trust organizations; however, this is not universally true. Most individual labor leaders are dedicated, trustworthy, and honest, and the labor movement often pursues social interests rather than narrow, self-serving ones. For example, unions advocate for worker protections, such as minimum wages or health and safety rules, that undermine the rationale for workers to organize a union. It is nonetheless true that most unions form in reaction to abusive management, and that unionizing a company rarely improves workplace trust. Relatively few labor leaders establish high-trust, positive-sum relationships with senior business leaders, although some do.

How will AI tools affect integrity and trust?

Software and systems that leverage artificial intelligence to automate tasks, analyze data, make predictions, and enhance decision-making processes have exploded. ChatGPT reached a million users in its first five days. It now has 400 million weekly users and is expected to reach a billion users by the end of this year, making it the fastest-growing technology in history.4 In addition to ChatGPT, Gemini, Perplexity, Grok/x.ai, Deepseek, and Claude are also experiencing rapid growth. Countless AI-powered applications tailored to specific industries, functions, or problems are only a few steps behind. If there can be a technology tsunami, this one is about to hit.

As AI tools infiltrate every American institution and workplace, it is crucial to consider whether they will foster trust or erode it. Currently, there is little reason to assume that AI tools will increase confidence in American institutions. In many cases, they may do the opposite. Let’s revisit how this technology is likely to shape trust in the five institutions we examined earlier.

Academia. AI tools could increase trust in academia if they improve research reproducibility, for example, by verifying data or flagging statistical flaws. AI-driven tools could strengthen peer review by making it more rigorous and transparent. Carefully designed, it could improve hiring, tenure, and admissions decisions. But AI tools can also mass-produce low-quality academic papers or flood journals with synthetic content. They can create opaque, algorithmic scoring for admissions or funding decisions. Currently, AI tools are being used to enroll bogus students and steal an estimated one-third of California Community College Pell Grants.

Politics. In politics, AI tools could increase trust if they help streamline cumbersome procurement and construction processes or are used for civic transparency by summarizing bills, flagging corruption, and credibly fact-checking political claims.

However, these tools can further erode trust if deepfakes and AI-generated misinformation overwhelm online information sources, or if microtargeted persuasion and synthetic propaganda become standard campaign tools that prevent voters from distinguishing between actual politicians and those generated by AI tools. Deepfakes are already impossible for most voters to spot. An American president who promotes as real pictures that are obviously photoshopped only worsens the problem.

Media. AI tools might increase trust in media if used to enhance investigative reporting by extracting public records, analyzing lengthy FOIA documents, or debunking false claims quickly and widely. However, these tools will erode trust if AI enables content farms to flood the internet with clickbait, partisan misinformation, or fabricated facts, or if news personalization reinforces filter bubbles.

Business. Will AI tools increase trust in business? If companies use it to improve service reliability, reduce fraud, and ensure compliance, it might. Or if AI tools make lending or hiring decisions more explainable and consistent. Or if they challenge leaders to think more deeply about the ethics or morality of business decisions.

These tools can obviously decrease trust if used to secretly monitor workers or customers, or to create airline-like pricing algorithms that are so opaque as to be untrustworthy. They will reduce trust if companies hide behind AI tools to evade accountability (“the algorithm did it”). Tools that are customer-facing and auditable might increase trust. Those that are a faceless tool of control, exploitation, or opacity will generate backlash.

Unions and workplaces. Can AI increase union effectiveness or trust? Some tools might help track workplace safety more precisely, organize more efficiently, or monitor employer abuses. However, most unions will focus on whether AI augments or replaces human work, and on how much voice workers have in deciding how these tools are deployed. Unless labor is actively involved in AI deployment, it is likely to worsen an already low-trust environment.

AI doesn’t operate in a vacuum. In low-trust societies, people are more likely to suspect that AI is biased, weaponized, unaccountable, and controlled by elites that serve their own interests. In higher-trust societies, AI might be seen as a neutral or benevolent force. However, in the US, where institutional trust has declined steadily for decades, the default attitude toward AI will likely be one of deep skepticism.

America needs to pay close attention to how transparency, disclosure, and democratic oversight affect popular trust in AI tools. If deployed opaquely, extractively, or manipulatively, these powerful and valuable tools will accelerate our crisis of declining trust and further erode confidence in democratic politics, media, and the workplace. Without thoughtful business and public leadership, effective disclosure norms, and robust democratic oversight, AI tools will continue to erode American institutions — and may do so very rapidly.

Musical Coda

Kenneth Arrow, Gifts and Exchanges, Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1972, p. 357. Quoted by Scott Sumner here. Arrow made pioneering contributions to general equilibrium theory, welfare economics, social choice theory, and information economics. He won the Nobel Prize in 1972. (Fun fact: he is one of Larry Summers’ two uncles who have earned the Nobel Prize in Economics.)

ChatGPT was launched in 2022 and is expected to reach a billion users within three years. For comparison, it took TikTok over 5 years, WeChat 7.1 years, Instagram 7.7 years, and YouTube, WhatsApp, and Facebook more than 8 years to reach one billion users.