Universities Created a Perfect Storm

...and have now sailed right into it.

American universities are suffering an identity crisis that has created a perfect storm and led them to sail blindly into its vortex. Four-year colleges and universities are among the most change-resistant institutions in the world, but few will emerge from this crisis unscathed.

They mismanaged costs. Rather than controlling rising costs, four-year colleges tripled tuition after adjusting for inflation between the 1960s and the early 2020s. As student debt exploded, many people suddenly questioned the value of a college degree.

They misunderstood inequality. Rather than reducing tuition and investing in college preparation for disadvantaged students with strong scholastic potential, 80% of colleges began admitting students without requiring standardized test scores. This put upward pressure on high school GPAs and led to massive grade inflation.

They unwittingly promoted mediocrity. When applicant quality degenerated, colleges could have demanded that high schools do a better job of preparing and sorting talent. Instead, they admitted unqualified undergraduates through dubious early-admissions programs and accommodated an explosion of requests for special academic disability study and testing arrangements.

They tolerated persistent ideological bias. Universities are and always will be bastions of liberal thought, but they need not become citadels of left-wing politics. To be sure, Trump would have waged a culture war against elite institutions regardless, but college administrators made his job much easier by mishandling violent campus protests.

They deliberately diluted talent signals. A college degree still signals something to employers, especially for selective schools and demanding majors, but it carries less standalone weight than it did 10–20 years ago. Often, a student must now reinforce their degree with evidence of concrete skills and experience. As companies turn to AI agents to manage the tsunami of AI-generated job applications, these agents are filtering for college degrees in ways that are opaque and difficult to interpret.

Many of these changes emerged from deeply progressive values. Most colleges and universities pride themselves on being engines of social mobility. They instinctively dislike social and economic inequality and want to reduce it by increasing access to higher education. For example, many faculty view the GI Bill, which enabled tens of millions of Americans to attend college, as having created the postwar middle class ex nihilo.1

But instead of building real, portable capabilities, many universities have yielded to the temptation to certify incompetence and reduce the value of their degrees in the eyes of the public and the marketplace. They have allowed grade inflation to conceal learning losses. They abandoned standardized testing in the name of preventing discrimination. They wildly expanded early decision admissions and the accommodation of dubious undergraduate learning disabilities. The ambivalence of most universities about their core mission and the lack of alternatives to bachelor’s degrees in the labor market have made these problems much harder to solve.

University of California Faculty Sound the Alarm

UC San Diego is highly selective. It attracts top applicants and admits only one in four. Last month, a report from the UCSD faculty documented that many recent students are shockingly unprepared for undergraduate work. The faculty noted that, since the pandemic began, an astonishing number of students lack basic reading and math skills.

Before 2020, only one-half percent of newly admitted students could not do junior-high level math (“If you have 9 pennies and nine dimes, how many coins do you have?”). That number is now over 12%. A quarter could not answer (“7 + 2 = [_] + 6”). More than a fifth of entering students now fail to meet basic writing requirements.2

To be sure, pandemic learning loss affected applicant quality across the board. With the best of intentions, California shut down its schools too quickly and for too long. But most of the problem stems from falling admissions standards. The UC system eliminated standardized test requirements in 2020, making grades count far more towards admissions decisions. This increased pressure on high school teachers to award A’s, even for poor or mediocre performance. Preposterously inflated grades, essays, and reference letters composed by LLMs, and the absence of standardized test scores made it difficult for admissions departments to determine applicants’ academic readiness. As Derek Thompson observed in a recent podcast, “The age of grade inflation is also the age of achievement deflation. We are giving more and more A’s to students who are learning less and less.”

The UCSD faculty report declared a five-alarm fire: so few incoming students can be placed into college-level precalculus that UCSD has had to expand remedial math thirty-fold. Whereas once remediation programs were to “fix gaps in high-school Algebra II,” they must now “rebuild grades 1–8 fundamentals.”

The faculty would never put it this way, but they are demanding that their elite educational institutions become more elitist by emphasizing excellence and increasing meritocracy. They are right.

Increasing Access By Lowering the Bar

In New York Magazine, Andrew Rice details the collapse of public education in America. On standardized national tests, 40 percent of fourth graders and a third of eighth graders failed a standard reading exam. Three-quarters of high school students were unable to calculate the total of a six-item restaurant bill and add a 20 percent tip.

Rice reviews the policy decisions that led to the collapse of high-quality public education in America.

From the late 1990s to about 2013, math skills in the U.S., as measured by test scores, rose steadily and rapidly, in part due to federal education policies focused on school accountability. The bipartisan 2001 No Child Left Behind Act required states to use standardized tests as a metric of success and penalized states for failing to meet those standards.

Howls against “teaching to the test” were widespread and reasonable, since states faced the risk of having to hold back large numbers of students. As a result, President Obama began to excuse some states from federal requirements. The Every Student Succeeds Act codified some of these exemptions in 2015, including a reduced emphasis on standardized testing.

Many other things were going on, of course. Mobile phones and social media began to consume the lives of young students. But overall, public schools across the country lowered their standards in the mid-2010s. They made courses easier and passed many more students who had not mastered the material. Many states also allowed students to skip classes entirely, making their curricula much easier. Oregon reports that a third of its students now chronically miss school.

Was this simply another example of progressives failing to deliver on promises that they had not thought through very well – as has happened in housing, municipal services, urban crime, energy infrastructure, or immigration? If so, they could simply acknowledge that the activists who removed standardized tests were mistaken and reinstate the SAT or ACT. Problem solved.

With Noah Smith, however, I suspect that our problems run much deeper. Progressive activists, who are never scarce on college campuses, have undertaken a deeply misguided effort to correct pervasive economic and social inequality by lowering the bar. They hope that doing this will reduce inequality stemming from the uneven distribution of talent and conscientiousness. The UCSD report shows that this effort has backfired horribly.

Disabled or Unprepared?

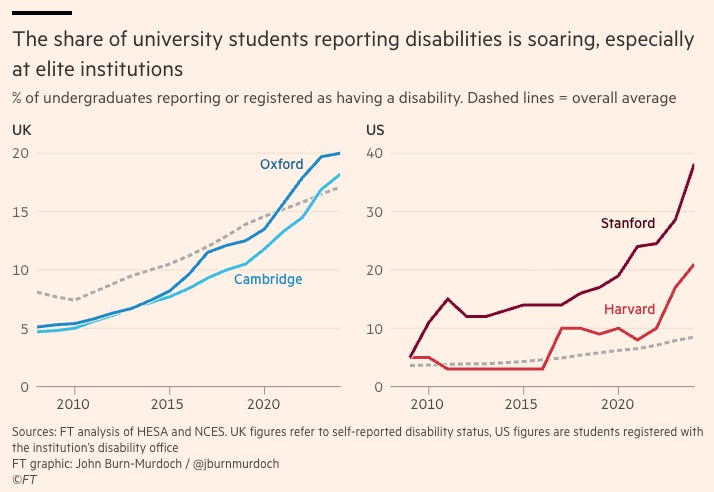

How do students who are manifestly unprepared for college cope with being tossed into a demanding academic environment? Many declare themselves disabled. Writing for this week’s Atlantic magazine, Rose Horowitch reports that in 2009, five percent of undergraduates at Harvard and Stanford declared themselves disabled. Today, 21 percent of Harvard students and 38 percent of Stanford students request special academic accommodations, especially extra time on tests and papers, by claiming a disability that was rarely evident in high school. In the FT, John Murdoch-Burns finds this trend widespread across many OECD countries.3

The Early Decision Racket

Early decision admissions programs have exacerbated the situation. These were once niche measures taken by a few very selective schools. The deal was that if a student applied early and pre-committed to accepting an admission offer, the school would render an early decision. Students avoided the stress of multiple applications and, in some cases, benefited from lower admission standards. Colleges received “first dibs” on talented high school seniors and could lock in applicants without making a financial aid offer. Moreover, they achieve a 100% yield on every early decision.4

“Yield” is the share of students who accept an offer of admission. It weighs heavily in most college ranking systems because it represents a market test: if 75% of regularly admitted students elect to attend UC San Diego, but only 60% choose to attend UC Merced, then, all else equal, San Diego ranks higher.

Admissions officers and university presidents (whose pay is often tied to their school’s rankings) recognize that students admitted via early admissions yield 100% because they must precommit to attend. To juice their yields, many schools have expanded these programs. According to a recent New York Times op-ed that termed the practice “a racket” and proposed to ban it, “many top schools reserve half to three-quarters of their entering class for those willing to submit to these restrictive terms.”

Not only are colleges exploiting the shift in bargaining power that happens once students get an admission offer, but some schools have retaliated against students who renege on their early decision agreement. After applicants reportedly failed to honor their early decision commitments, Tulane blacklisted from early admission the entire next year’s graduating class from the offending students’ high schools.

What are Universities For?

Matt Yglesias recently cited outspoken UCSD faculty members who had no objection to low-performing undergraduates (or to faculty ideological bias) and argued that this simply indicated a need for more funding. He contrasted the political challenge facing universities with the one facing police departments in the wake of the 2020 George Floyd killing.

Police attract conservative professionals, much as universities attract lefties. Cops were often tone-deaf to concerns in blue cities about police malpractice during the pandemic. But cities and police departments shared a goal: to make cities safe and orderly. They resolved a series of specific disputes in pursuit of this shared goal.

Universities, in contrast, have lost a coherent sense of their mission, which allows controversies over admissions, grading, and accommodations to metastasize because universities can’t clearly say what they’re trying to accomplish.

In part, this reflects a centuries-old tension between the research and education missions of a modern university. Faculty at top schools have strong incentives to maximize research and minimize classroom teaching. Although many care deeply about teaching and are devoted to their students, they earn tenure and promotions by publishing high-quality peer-reviewed research. (The quality of this research is increasingly under scrutiny. Long before Trump turned research grants into culture war ammo, the quality of academic research was under attack for not consistently replicating.)

The tension between broad education and career training has also muddled university missions. As tuition prices rose before 2023, many students and their families had come to place less value on what we used to call “a solid liberal arts education.” To justify rising levels of student debt, they sought an undergraduate degree that would provide concrete, marketable skills in fields such as computer programming, accounting, or nursing.

Many universities have embraced what they believe to be business practices, including highly paid, expansionist, and self-preserving administrators, brand strategists, risk managers, and HR professionals. The result hasn’t been better research or teaching. Many elite universities have prioritized prestige, expansion, and revenue generation over scholarship and education. The worst of them are lifestyle companies with a school attached. As the mission drifts, success becomes impossible to measure, and administrators work on looking successful rather than being successful.

Employers are badly served but lack credible alternatives. Employers consistently indicate interest in alternatives to a bachelor’s degree, yet they continue to rely on college degrees even as the signal a degree sends has faded.

Like many people, I favor removing degree requirements from job postings where they are not strictly relevant. However, research by Harvard’s David Deming and labor market researchers at Burning Glass and Harvard Business School all found that without legible, trusted, and portable non-degree credentials, the trend toward “skills-based hiring” fails. Employers who are happy to remove degree requirements hire college grads anyway because so few career credentials below a BA or BS match the ability of a college degree to serve as a nationwide career passport. Absent credentials with consistent quality, content, and names, employers can’t price what they’re buying. As large language models take over both applications and screening, this problem becomes even harder to clarify. Earlier this year, I wrote about this problem in more detail.

Policy Fixes

Progressives concerned with raising the incomes of bottom-quartile students and workers need to embrace strong K-12 and higher-education standards and build credible non-degree pathways that employers actually recognize.

Do not blame the fever on the thermometer. It is very easy for people who find inequality morally intolerable to treat standardized tests as the problem. They are blaming the data, not the underlying reality – precisely what Trump did when he fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics because he did not like a jobs report. Hiding measurements never improves an underlying condition. Standards are not the enemy.

Define “A”s. When grades inflate, but mastery does not, you get neither equity nor excellence; you get fake credentialing. A Washington State analysis summarized by Fordham shows that failing grades collapsed and A’s surged during the pandemic. A’s in math rose from 33% to 56% and math GPA from 2.6 to 3.2 during 2020. These “equity” policies that quietly remove consequences—no zeros, no failing, softened curricula, lower admissions signals—did nothing to protect disadvantaged students. They stripped them of the only thing that can reliably increase their life chances: actual skill.

I am personally familiar with this problem. Before the pandemic, I ran a business school where faculty routinely awarded “A” grades to two-thirds of the students. An “A” grade meant nothing, nor did honors degrees based on them. Grade inflation was unfair to top students, so we defined the grade to mean the top quartile. As a result, we permitted faculty to award an “A” to no more than 25% of students in any course. Many professors howled, and naturally weaker students hated it. But when an A grade suddenly meant top-quartile performance, student focus and motivation changed.5

Set high standards and embrace “truth in credentials.” Teachers should advance students only when they have mastered the material. Mastery may or may not involve grades.

The Khan Academy is obsessed with this. They have demonstrated the benefit of a mastery-based system. Instead of traditional grades, lessons emphasize deep understanding, with students demonstrating proficiency through practice rather than advancing after a fixed period or score. Teachers can set custom grading rubrics (e.g., points for time spent, mastery levels), but the platform itself tracks progress through “Mastery Goals,” “Streaks,” and skill points, allowing personalized learning paths. Students get more practice if they struggle and can advance quickly as they fully grasp concepts.

Attendance standards also matter, since nobody learns what they never encounter. Non-attendance and chronic absenteeism need to carry real consequences for both parents and students.

Ban Early Admission. It has become a back door for students from wealthy families who can afford to be indifferent to financial aid decisions. Applicants should be able to evaluate financial aid offers before deciding where to attend college, and they should face common standards regardless of an offer’s impact on a school’s admissions yield. College admissions should not force 17-year-olds to gamble with their educational future.

Make non-degree credentials legible, portable, and nationally credible. Doing this requires state and federal institution-building. We need to scale apprenticeships, which today are small and bespoke. We should create stackable, standardized career pathways with common curricula and shared “skill language,” and use federal funding/standards to enable credentials to travel across state lines as a BA does. As a prototype, consider models such as Virginia’s FastForward program, which provides short-term workforce credentials with structured pathways and has demonstrated meaningful earnings gains.

Specialize. The general-purpose, 18th-century liberal arts university is under extreme pressure. Many schools need to specialize. Some should serve primarily as research hubs. Others should mainly educate students, sometimes working closely with industry to build technical mastery and earn nationally recognized credentials. All should produce grades that clearly signal performance and enable employers to better understand what graduates do and do not know.

Schools need to recognize that when their mission becomes fuzzy, their decisions become more political: admissions standards, grading norms, accommodations, classroom expectations, and even whether learning outcomes matter.

The political, demographic, and technological storms buffeting American colleges and universities are severe. A shockingly short-sighted president has turned against higher education and slashed federal research grants. Not only are fewer high school seniors graduating each year, but in many regions, fewer are enrolling in college. Large language models have neutered academic honor codes and rendered admissions essays useless. China now produces very high-quality scholarship.

Universities should never abandon their goal of helping to reduce income inequality, but they need to recognize that ultimately, skills matter more than credentials. When teachers inflate grades starting in kindergarten, and universities lack discipline in what they require and measure, students experience their educational journey as “credential theater.” Employers respond by deprecating the value of degrees or, worse, by using them as blunt proxies to exclude talented people who avoided the college charade in the first place.

For me, the perfect storm buffeting American universities is personal. My family tree is crawling with educators, including my mother, wife, and son. Our family bleeds the blue and gold of UC Berkeley and the maroon of the University of Chicago. American universities have powered this nation’s social mobility and global leadership. I very much want them to continue to do so.

CODA

Thanks to the leadership and global reputation of musicians Owen Dalby and Meena Bhasin, Noe Music consistently attracts emerging musical talent to San Francisco. I am a huge fan, and delighted that they are finally putting some of their legendary concerts online. If you are in the Bay Area, I urge you to check out these concerts.

Here, Grammy-nominated pianist, accordionist, composer, and educator Sam Reider, along with Jorge Glem and Munir Hossn, perform Dylan’s bitter farewell to Suze Bartolo. The rock ‘n roll accordion finale starts at 5:00.

The GI Bill was one of the central engines of the white postwar middle class, but it amplified and reshaped trends that were already underway rather than creating them from nothing. Economic growth, pent‑up wartime savings, strong labor unions, and U.S. global dominance meant that an expansion of the U.S. middle class would have occurred in some form even without it, though perhaps on a smaller scale, with a less educated and more unequal citizenry.

These are not trick questions. You have 18 coins, and the second answer, obviously, is 3.

Murdoch-Burns notes that this is not primarily a “story of improved identification and care for young people who previously lacked help and support… First, the applications of systems designed for fixed and clearly defined categories of impairment to (often invisible) conditions that sit on a spectrum and leave room for interpretation. The bulk of the rise in special support for youngsters is cases of non-profound autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), plus anxiety and mental health, all of which have flexible diagnostic criteria. Where detailed data is available, we consistently see mild, not severe, cases driving the rise.”

Early decision is not the same as early action or rolling admissions, which merely expedite the admissions process without imposing restrictions.

It was plainly the right thing to do for students, but perhaps not for me. The school was deeply and irrationally committed to making decisions based on weekly student satisfaction polls. They fired me when the numbers dropped.

Very well done, Marty. The unspoken by-product of lower standards is that we are failing to fully develop the most capable students. The loss of productivity of the top quartile of the most innately talented students will have profound consequences.

Great post! But I think the rise in "disabled" students might be connected to an increasing tendency for young people to identify as "neurodiverse" and claiming disorders like ADHD or even autism. Schools should apply more strict tests to the people claiming these otherwise they are effectively cheating by having the extra time. Also a related reform would be making non college credentials more portable and more accepted by hiring organizations.