Trade With China Did Not Destroy American Manufacturing or Our Middle Class

The left and the right agree on China and trade. Both are wrong.

Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump tell a similar story: Once upon a time, the United States was a manufacturing powerhouse where unionized factory workers built a broad, prosperous middle class. Then came globalization, particularly trade with China, which gutted our industrial heartland, shipped good jobs overseas, flattened wages, and left behind a hollowed-out economy where only the college-educated thrive and the working class struggles in low-wage service jobs.1 This narrative has become so entrenched in our national consciousness that it shapes political campaigns, drives trade policy, and fuels populist movements across the ideological spectrum.

There's just one problem: The data tells a much different story.

The Myth of America's Manufacturing Apocalypse

Many Americans believe that the opening of trade with China, combined with neoliberal (meaning pro-globalization) policies championed by both parties, created a devastating "China Shock" that decimated American manufacturing towns. Workers lost high-paying factory jobs and were forced into low-wage service work. The middle class collapsed, inequality soared, and the American dream withered for all but the coastal elites. This storyline has been repeated so often that it feels heretical to point out that it is fundamentally distorted.

As usual, this account contains a kernel of truth. There is no question that globalization and trade with China hurt American manufacturing and created genuine hardship for some two million workers and communities. We devoted far too little of the benefits we gained from trade to addressing the very real costs that came with it. However, the broad narrative of trade-induced economic devastation is more myth than reality. The decline of American manufacturing had multiple causes. The middle class remains surprisingly resilient. America's economic evolution followed similar patterns to developed nations with very different trade policies.

America is not highly globalized.

Most of what America consumes is made here, and most of what America produces is consumed here. This fundamental economic fact hasn't changed as much as the popular narrative suggests.

America is far less globalized than most people think. Noah Smith points out that the US is already a closed-off economy compared to most rich nations. As a share of GDP, total imports are much lower in America than in most other developed countries, even lower than in China.

When politicians and pundits discuss America's economic challenges, they often point to a flood of cheap Chinese goods overwhelming American markets. Yet the trade deficits that generate so much political attention represent an even smaller slice of our economy. Smith calculates that US imports of manufactured goods minus exports amount to about 4% of GDP annually, while our much-discussed trade deficit with China is approximately 1%. These aren't rounding errors, but they're hardly economy-shattering figures.

Even more revealing is how little American manufacturers depend on Chinese inputs. China produces only about 3.5% of the intermediate goods that American manufacturers use in production. The image of American factories entirely dependent on Chinese parts simply doesn't match reality.

Trade deficits do not drive deindustrialization.

Suppose we could wave a magic wand and eliminate trade deficits entirely. Would manufacturing come roaring back? No. Economist Paul Krugman estimates that even if we completely eliminated the manufacturing trade deficit and replaced imports with domestically made goods on a one-to-one basis, manufacturing would only rise from its current 10% of GDP to about 12.5%.2 That would return manufacturing to 2007 levels — hardly a restoration of America's mid-20th-century manufacturing prominence.

Forces beyond trade have been driving manufacturing's declining share of the economy. In other developed nations, manufacturing has declined regardless of their trade balances.

France saw its manufacturing share decline despite running trade surpluses in the 1990s and 2000s.

Germany has a larger trade surplus as a share of its GDP than China, but it has seen a massive long-term decline in the manufacturing share of employment.

Japan has done its best to preserve its manufacturing employment since 2010.

Even China, which runs large manufacturing-driven trade surpluses with nearly everyone, is seeing manufacturing decline as a share of its economy and employment.3

While trade has played a role in reshaping American manufacturing, it's been a supporting character rather than the villain of our economic story. Technology (software, automation, and productivity gains from process improvements) accounts for 50-60% of the decline in US manufacturing employment. Trade explains only 20-25% .4

The Middle Class Has Not Been Hollowed Out.

Perhaps the most persistent myth about globalization is that it hollowed out the American middle class, leading to widespread income stagnation. This narrative of middle-class decline has become so deeply embedded in our political discourse that challenging it feels almost sacrilegious. Once again, however, the data tells a different story.

Americans are remarkably prosperous.

When we compare median disposable household income across developed nations, the United States significantly outperforms most other countries. This isn't averages skewed by billionaires; Americans in the median income distribution are doing well.

It surprises many people that middle-class incomes haven't stagnated over recent decades. Real median personal income has increased by about 50% since the early 1970s. This growth hasn't been as robust as in the past, nor as strong as we should want. And it has not been evenly distributed or without periods of stagnation. Nonetheless, a 50% increase over five decades represents slow but real economic progress of about .8%/year. It does not reflect decline.

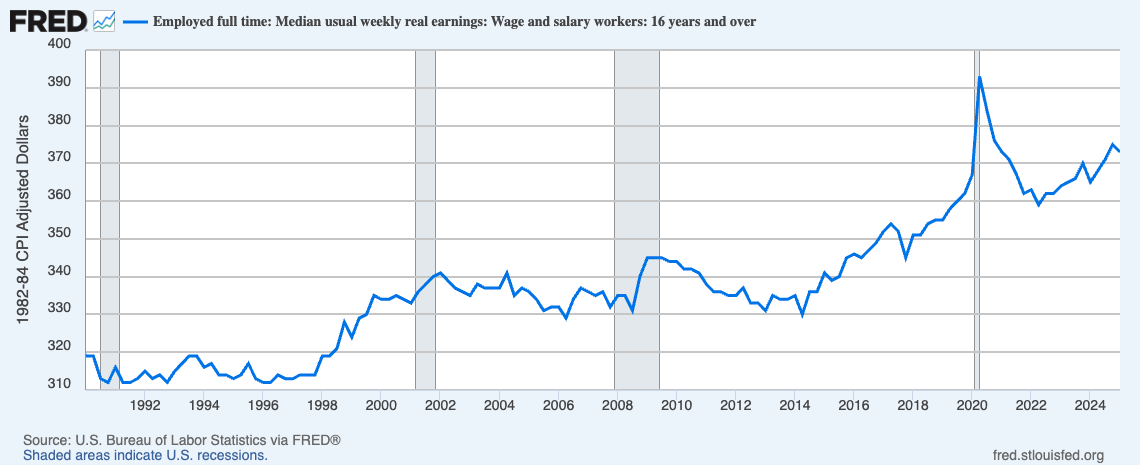

What about wages? Although wage growth has lagged behind overall income growth (income includes benefits, investment returns, and government transfers), real wages have grown substantially since the mid-1990s. Importantly, this wage growth resumed and continued despite increasing trade deficits and the "China Shock". We wouldn't see this pattern if Chinese imports were devastating American wages.

Many progressives, including me, look at the distribution of wage increases and notice that the incomes of the most highly paid have grown much faster than the median during this period. This is annoying, unfair, and in some cases, corrupt. Of course, it sometimes reflects scarce, valuable, and specialized skills. Currently, wages are very high for LLM engineers with deep experience in model optimization, deployment, and scaling.

Although wages at the top have grown, wages at the bottom have also grown nicely. Bottom-quartile wage growth is stronger than median wage growth, with wages increasing by over 40% since 1996. This represents a substantial reduction in income inequality – a major narrative violation in US political discourse. I bleed pixels arguing for even more wage compression, but for a low-wage worker, annual wage changes faster than the median represent a substantial improvement in living standards. Consider this data on changes in income deciles for the 30 years following 1979 vs the five years following 2019 from the pro-union Economic Policy Institute:

Many regions have recovered from the China Shock.

None of this denies that Chinese import competition hurts specific industries and regions. The careful China Shock research shows that parts of the country with sectors that faced direct Chinese competition suffered significant job losses and economic disruption. However, two important caveats apply.

The China Shock was bad, but limited. The 2 million affected workers represented only about 1.5% of the US workforce. Plant closures often devastated workers and their communities, but did not affect 98.5% of American workers. It was not a national economic apocalypse.

The China Shock was temporary. Perhaps more importantly, these regional effects haven't proven permanent. Even the poster children of deindustrialization, like Flint, Michigan, and Greensboro, North Carolina, have substantially recovered over the past decade. Wages for lower-income workers have increased in both areas, and middle-class wages have risen in Greensboro. Median incomes have recovered their economic health over the last decade, and this isn't just because people moved away.5

The Unexpected Evolution of the Service Economy.

If manufacturing jobs declined, but most Americans are doing better, what happened? The narrative around "service economy jobs" often implies that manufacturing workers were forced into lower-paid service work, flipping burgers or stocking shelves. That description was more accurate during the early 2000s, when many displaced manufacturing workers did indeed take lower-paying service jobs.

However, the 2010s and 2020s tell a different story. Research by David Deming and colleagues shows that over the last 15 years, the trend toward low-skilled service sector jobs has reversed. Americans increasingly seek higher-skilled professional service jobs in management, STEM, education, and healthcare.

Zoom out, and notice that this chart tells a familiar story. A dynamic US economy has always faced dramatic changes in employment. Jobs in the US have evolved, often profoundly, for more than a century. During the late 19th century, 80% of all US jobs were either in farming or blue-collar production, but by the 1960s, farming jobs were less than 10% of the total and falling sharply. Starting in 1950, the share of blue-collar production jobs fell from 40% to 20%. Professional, office and administrative, and other “services” jobs rose steadily during this time — although the office and administrative job share has been falling since 1980, and the share of jobs in retail sales is also declining. Overall, the shifts in US job categories in the last few decades don’t seem extraordinary in the historical record of the past century.

This suggests that former President Clinton's oft-criticized advice to get more education was correct. The average American has proven capable of adapting to knowledge work. And crucially, this shift is being reflected in wages and incomes.

Why The Myth Persists Despite The Data.

If the data contradicts the popular narrative about trade, manufacturing, and the middle class, why does the myth persist so stubbornly in our political discourse? There are several reasons.

There was real human suffering. When a factory closes in a town where it was the primary employer, the pain is immediate and visible, even if regional statistics eventually show recovery. No laid-off 55-year-old factory worker gives a damn about aggregate statistics or decade-long recovery patterns.

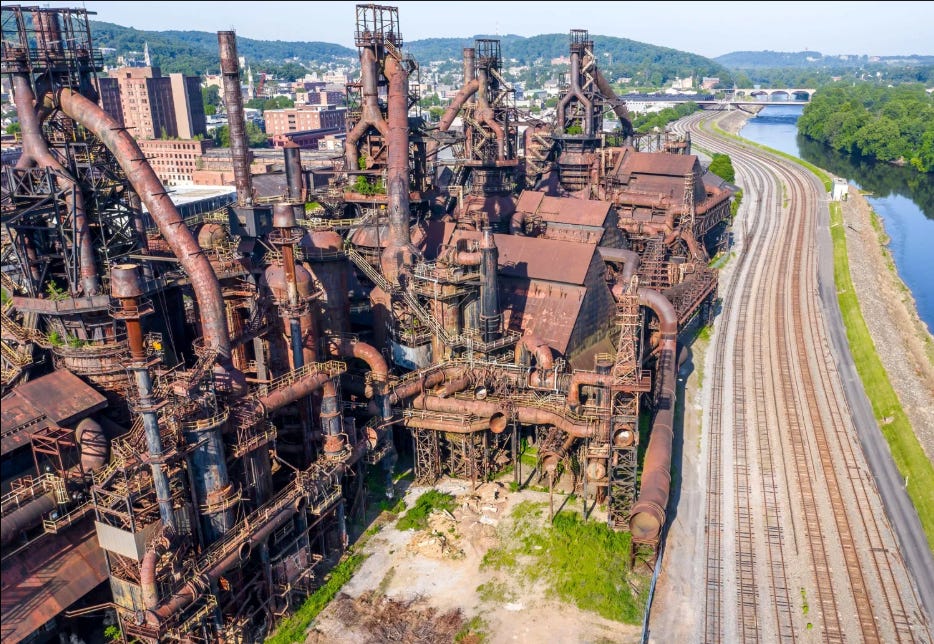

The Rust Belt rusted. Industrial decline is ugly. Abandoned factories and struggling former manufacturing towns create powerful imagery that statistics can't easily counter. To people living in crumbling towns, it is irrelevant that most Americans are steadily becoming richer.

We stagnated relative to the post-war period. Americans expect continuous progress and upward mobility. An economy that delivers modest but steady gains feels like stagnation compared to the exceptional boom years of the post-World War II era. We can and should grow much faster.

We romanticize and masculinize factory work. Factory work is better than no work. It pays the bills and beats farming, but nothing is glorious about it. I have worked ten-hour shifts in a thick raincoat, steamcleaning the equipment used to can green beans. I have operated loud machinery with repeat times reminiscent of Lucy and her chocolates. I ran equipment that made vitamins and other drugs that were impossible not to inhale. I briefly believed that the huge machine shop where I worked preferred to hire handicapped workers because so many men were missing fingers. Factory work improves as it becomes more technically challenging, and the friendships can be good. But now that service jobs pay more than factory jobs, there is no reason to glorify factory work.6

“China killed manufacturing” mobilizes people across the political spectrum. It fuels nationalism and protectionism for right-wing populists. For progressive populists, the narrative justifies stronger labor protections and government intervention. Both sides have incentives to perpetuate the story, regardless of its accuracy (or the effect it has on promoting hostility to Chinese-Americans).

Implications For Economic Policy

If our understanding of trade's impact on American manufacturing and the middle class has mainly been mistaken, what does this mean for policy?

Blanket protectionism is a bad idea. Targeted tariffs to reduce dependence on China in critical industries, especially defense sectors, make sense. However, even aggressive tariffs would barely increase manufacturing's overall share of the economy while potentially harming industries that depend on global supply chains.

Services now drive prosperity. Successful economic policy should focus less on restoring an idyllic manufacturing past (which was no more idyllic than the family farms many Americans longed for in the 1970s). Instead, we must focus on preparing workers for the professional service jobs that have become the real engine of middle-class prosperity. Investment in education, skill development, and the infrastructure of knowledge work deserves priority.

We need to support hard-hit regions. The United States has shamefully neglected communities and workers genuinely harmed by trade competition and technology. Instead of economy-wide protectionist measures, we need solutions for specific regions and workers tailored to their circumstances. Germany crowdsourced job placement: they paid a generous placement fee to anyone who found a job for a worker in a hard-hit factory town. It seemed to work, and it is the sort of thing we need to test.7

One solution: luggage. Relocation has always been an essential part of American industrial progress. When people want to move to a place with better opportunities, we need to make it easier, not harder, for them to do so. Fifty years ago, low-income workers were far more likely to relocate. Today, high-income workers move, and too many low-income families feel stuck.8

We need smart industrial policy. Manufacturing still matters, not because it's the only path to middle-class prosperity, but because it contributes to a balanced economy, national security, and innovative ecosystems of engineering practice. Smart industrial policy that builds competitive advantages in high-value, often export-driven manufacturing is more sensible than protectionist policies that try to reclaim the past. It sucked if you lost a good job in a Providence tennis ball factory, but the US is not going to be making tennis balls again until we build robots that can make them with almost no human touch. We need to be in the business of making robots, not hand-made tennis balls.

American Prosperity is Neither Linear Nor Simple

The story of China destroying American manufacturing and the middle class offers a simple, emotionally satisfying explanation for complex economic changes. However, by misdiagnosing our financial challenges, a false narrative can lead us to pursue ineffective or counterproductive policies.

The real story is messier but ultimately more hopeful: America has grown more prosperous despite manufacturing's relative decline. Manufacturing stuff with fewer workers has not hollowed out our middle class any more than farming with fewer people did during the twentieth century. Lower-wage workers have seen substantial gains in recent decades (I devote an unreasonable portion of this Substack to the need for further productivity and income gains.) The disruptions caused by global trade have been real but limited, and even hard-hit regions have shown resilience and an admirable capacity for recovery.

None of this means America doesn't face serious economic challenges. Inequality remains a pressing issue. We have shamefully left regions and workers behind. Our infrastructure needs renewal. We lag China in industries like drones and missiles critical to national defense. However, addressing these problems requires an accurate understanding of where we've been and where we are, not a mythologized version of economic history that exaggerates trade's negative impacts while ignoring the complex evolution of American prosperity.

We must tell the story of American manufacturing and the middle class with its nuances intact. Only then can we craft policies that build on our strengths rather than fighting imaginary dragons from a misremembered past.

Musical Coda

Rita Hayworth and Fred Astaire dance to Led Zeppelin. Yeah, really.

Examples are not hard to find. This week, I would point to conservative Oren Cass and liberal Joe Nocera, writers I admire.

Krugman, who got a Nobel Prize for his work in trade economics, offers the following: “Last year the US ran a manufacturing trade deficit of around 4 percent of GDP. Suppose we assume this deficit subtracts an equal amount from spending on US-manufactured goods. In that case, what would happen if we somehow eliminated that deficit?

It would raise the share of manufacturing in GDP — currently 10 percent — by less than 4 percentage points, because manufacturing firms buy many services. A rough estimate is that manufacturing value-added would rise by around 60 percent of the change in sales, or 2.5 percentage points, implying that the manufacturing sector would be around a quarter larger than it is.

But…manufacturing as a share of employment has fallen about 17 points since 1970. Complete elimination of the trade deficit would undo only around 2.5 points of that decline. So even if tariffs “worked,” which they won’t, they would fall far short of restoring manufacturing to its former glory.”

China’s manufacturing employment share peaked at almost 30% in 2014 and has trended down slowly since then.

Other factors influencing the decline of manufacturing employment include shifts in domestic demand away from goods (towards services), energy costs, regulation, macro trends, etc. Debates continue, but no researchers attribute manufacturing job losses primarily to trade. Acemoglu, Autor, et al. (2020) estimated that trade with China from 1999–2011 caused a loss of 2–2.4 million jobs, but much of the overall decline was already underway before China’s WTO accession. Charles, Hurst, and Notowidigdo (2016) suggest that long-run trends like demand shifts and productivity improvements explain most of the decline. The McKinsey Global Institute (2017) attributes roughly 80–85% of job losses in manufacturing since 2000 to productivity gains, not trade.

Flint's population has remained relatively stable while Greensboro continues to grow. North Carolina still has many low-wage towns like Greensboro, but Texas, West Virginia, Louisiana, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Mississippi all rank below North Carolina, and none were hit especially hard by the China Shock.

As of March, the average manufacturing sector job paid $35.16/hour compared to the average private service-providing job, which paid $35.81. Since public sector jobs average $63.46/hour and consist entirely of services, the average service sector job pays more than the average manufacturing job. The standard caveats about using averages apply here in force.

Germany created vouchers to enable a private market for relocation services. They targeted hard-hit communities of displaced workers. Any person or agency could earn money by helping a displaced worker find a job. The payment ranged from $1,700 to $2,800 and came partly from the unemployment fund and the hiring employer. The amount paid depended on the duration of each worker's prior unemployment. An agent earned more money by placing the more complex cases. The program only paid to help displaced workers from particular distressed regions find employment and excluded workers who already held jobs. Unlike American Trade Adjustment Assistance, the German experiment did not worry about why a person had lost his or her job. To prevent scams, part of the payment came after the worker had been on the job for six months.

Germany formally evaluated this program using a valid control group. Researchers determined that the program promoted mobility, placement, and efficiency. Although it saved money, they concluded they needed to pay agents more to place the highest-risk workers. (Note that this experiment involved only a relocation and employment bounty, not a wage subsidy, relocation assistance, or income support.)

Economist Ernesto Moretti notes that about a third of Americans live in a state other than the one they were born in, and about 40 percent of US households change addresses every five years. College graduates move the most often, high school graduates less, and dropouts the least. He proposes mobility vouchers that would cover some relocation costs. Instead of encouraging out-of-work residents to remain in depressed labor markets, the government could provide incentives to some to relocate to stronger markets. This would help unskilled workers who want to move but lack the cash to cover upfront costs. By increasing the number of workers willing to relocate, mobility vouchers would benefit those who leave and end up with a better job elsewhere and those who stay and end up with a better chance of finding a job.

This is a good article. Many of these points were first made more than 30 years ago (as in my article "The Enemy is the Mindset"). It is disappointing that the same outdated framework is still very operative politically today. It is likely to die hard even with the compelling facts. BTW, I did an analysis previously that showed that the perceived pressure on disposable income was caused by the increasing share taken by healthcare and housing costs (both the result of bad policy.) which offset the overall gains in disposable income.

Marty, your article provides a compelling reevaluation of the widely held belief that trade with China decimated American manufacturing. At IntelliSell, our analyses indicate that while globalization and China’s WTO accession did impact certain sectors, the broader decline in manufacturing employment is more attributable to factors like automation and shifts in consumer demand.

Your emphasis on the multifaceted nature of manufacturing job losses aligns with our findings. It’s crucial to recognize that while trade played a role, technological advancements and productivity gains have been significant drivers of change in the manufacturing landscape.

Thank you for shedding light on this nuanced topic and challenging prevailing narratives.

—IntelliSell Team

Transforming market noise into strategic intelligence for manufacturers