The US Should Set the Terms of Competition with Chinese EV Transplants.

...And Why Chinese Carmakers May Offer Organized Labor a Valuable Opportunity

Pro-American and pro-labor folks like me operate under a set of incomplete economic beliefs.

They believe that trade with China devastated the American industrial heartland and hollowed out US manufacturing.

They have noticed that non-union auto assembly transplants from Japan, Korea, and Germany have provided automakers with a significant foothold in the American South that is not unionized.

They have concluded that heavily subsidized electric vehicles (EVs) from China pose an existential threat to US automakers and autoworkers’ unions, which justifies the tariffs on these cars imposed by both Biden and Trump.

These ideas are not entirely wrong, but they are misleading enough to fog policy thinking and mask opportunities for America and American unions to take valuable initiatives. Specifically,

The “China Shock” research is excellent. It demonstrated that the shock was severe for some regions and families. Subsequent research shows that the shock was short-lived, geographically limited, and less significant than technology as a driver of American deindustrialization.

Chinese automakers may be less opposed to labor unions than legacy transplants. Since 2013, workers who assemble electric buses in California for China’s largest EV manufacturer have had an active union, a comprehensive training program, and a community benefits agreement.

Low-cost Chinese EVs are already available in Mexico, and Canada may allow them in retaliation for mindless US tariffs. American unions should support manufacturing them in the US if China agrees to domestic content, security, and collective bargaining arrangements.

Let’s dive in.

It Starts With Bicycles

The humble bicycle has given rise to dozens of innovative technologies. In 1888, John Boyd Dunlop invented air-filled tires for his kid’s bike. Comfortable tires opened cycling to the public, especially women. They worked so well on cars and motorcycles that brutal rubber empires sprang up to support a new tire-making industry. Carbon fiber technology originated in bike frames and quickly spread to the aerospace, automotive, and sporting goods industries. The technology that underlies quick-release systems, ski bindings, and power meters was initially developed for bikes. In developing countries, bicycles inspired the development of pedal-powered machines for irrigation pumps, corn shellers, and boats. Two bike mechanic brothers taught the world to fly.

However, when the whole story is told, electric bicycles will surely be the highest-impact technology to emerge from bicycles.

Americans began fiddling with electric bicycles just after they invented rubber tires.1 Early models were limited by the expense and short lifespan of their batteries. With the development of nickel-cadmium and later lithium-ion batteries in the 1990s, interest in e-bikes surged. By the late 1990s, large companies were producing modern e-bikes. By the 2010s, environmental concerns, urban congestion, and government incentives had driven an explosion in e-bike use in Europe and Asia.

E-Bikes in China. By the late 1990s, pollution had become a serious concern in China, so government policies began to favor the use of e-bikes over motorcycles with two-stroke engines. China banned gas-powered scooters in major cities and offered incentives for companies to build electric bikes and scooters. These policies, combined with urbanization, rising fuel prices, and advances in battery technology, led to explosive growth. Sales of electric bicycles and scooters grew from 56,000 in 1998 to over 21 million a decade later (for comparison, China sold only 9.4 million cars in 2008).

Chinese policy propelled e-bike growth. Cities either banned gas-powered motorcycles altogether, stopped issuing motorcycle licenses, banned them from major roads or downtown areas, or auctioned a limited number of motorcycle license plates. According to the Society of Automotive Engineers of China, the use of motorcycles is now completely banned or severely restricted in over 90 major Chinese cities. Electric bikes were categorized as non-motor vehicles and exempt from these bans.

From e-bikes to EVs. By the 2000s, government policies supporting e-bikes had become part of a broader strategy to promote electric vehicles, reduce urban pollution, and create a regulatory and consumer environment that was favorable to the growth of the entire electric vehicle sector.2

China’s timing was good. Motor and battery technology improved substantially during the 1990s. Because intellectual property protection was weak, fierce copycat competition drove e-bike prices down just as gas prices increased and rural workers flooded into urban areas. This led China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) to include e-bikes as one of the 10 key scientific development priority projects in the country's Ninth Five-Year Plan in 1995. By 2000, the NRDC had formally expanded its support for e-bikes to include electric vehicles.3

By 2007, China was investing over $300 million annually in the development of new energy vehicles. Over the past decade, this figure has grown to exceed $230 billion in total support. These policies, combined with non-monetary support such as procurement contracts and favorable regulatory conditions, enabled China to rapidly scale its EV industry and establish a robust network of specialized suppliers. China is now the world’s largest producer and the largest market for electric vehicles.

Competition in the Chinese EV market is Darwinian. There were approximately 500 Chinese electric car manufacturers in 2019, but by 2023, only about 100 manufacturers selling over 200 brands remained in operation. One estimate projects that only 19 of these companies will still be profitable by 2030. This recalls the very early days of the US car industry during the 1910s, when at least 1,900 different companies built more than 3,000 different makes of American automobiles. Oakland, California, alone was home to five car companies.4

The US Freaks Out

In 2011, Tesla CEO Elon Musk laughed when asked about Chinese electric vehicle maker BYD (“Build Your Dreams”) on Bloomberg. He is not laughing now. In January of last year, he declared that Chinese car companies were the "most competitive", saying that “frankly, I think, if there are no trade barriers established, they will pretty much demolish most other companies in the world.” It is difficult to find any auto industry analyst who disputes this assessment. Many believe that allowing China to export EVs to the US would represent an “extinction-level event” for legacy American automakers.

Both Biden and Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles for straightforward reasons. Chinese EVs are significantly cheaper than those made in the US, mainly due to lower production costs and substantial government support. Their entry could force American factories to close, resulting in the loss of thousands of jobs, as has happened in the steel and solar panel industries. The US auto industry still remembers the market share losses to Japanese automakers in the 1970s and 1980s.

There are concerns that Chinese EVs could pose national security risks, including the potential for data collection due to the advanced connectivity features in modern vehicles. Because China controls a significant share of the global EV battery supply chain, it has leverage over critical inputs, making the US vulnerable to supply disruptions if China uses its position for geopolitical leverage.

Voluntary Export Restraints. In 1981, Ronald Reagan faced a similar problem because Japanese automakers were threatening the US Big Three: General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. Reagan successfully persuaded Japan to "voluntarily" limit its car exports to the United States. The idea was to provide the US auto industry "breathing room" to recover from financial difficulties and adjust to changing consumer demands for smaller, more fuel-efficient cars.

These so-called Voluntary Export Restraints (VER) provided short-term relief to the US auto industry. As expected, they also raised car prices for American consumers, creating profit windfalls for Japanese car manufacturers. In negotiating the VER, Reagan urged Japanese automakers to build factories in the United States. They did, and today, some 24 Japanese, German, Korean, and other “transplant” factories employ more than 400,000 Americans.

Should the United States Allow Chinese Transplants?

The strongest argument against allowing Chinese EV manufacturers to establish assembly plants ("transplants") in the US is similar to the case for banning these cars as imports. Chinese EV makers, backed by extensive state subsidies and dominant in battery and EV technology, would undercut US automakers with ultra-low-priced vehicles, potentially devastating domestic manufacturing and leading to significant job losses. (These are excellent cars. Ford CEO Jim Farley had an all-electric Xiaomi SU7 flown in from China. He calls the car “fantastic” and does not want to give it up.)

The case for allowing Chinese transplants is likewise straightforward:

Many more Americans would have access to affordable, high-quality EVs. These are simply better cars for most people, and they emit much less carbon.

Chinese EV plants would bring billions of dollars in investment and create tens of thousands of American manufacturing jobs, much as Japanese, German, and Korean automakers did decades ago.

Investments by Chinese companies would help expand the US EV supply chain, reduce dependency on imports, and make the US less vulnerable to global disruptions.

Sourcing components domestically and manufacturing batteries in the United States would also enhance national resilience.

The presence of Chinese firms would also spur knowledge transfer, partnerships, and licensing agreements that benefit American automakers and help the US close the technology gap with China.5

EVs assembled in the US would be subject to American labor, environmental, and safety standards, ensuring better oversight compared to importing finished vehicles from China. The US could permit Chinese investment under strict conditions that require domestic sourcing, adherence to US labor standards, and rigorous national security reviews, similar to those conducted by the Committee on Foreign Investment (CFIUS).6

Barriers. There are genuine challenges for any Chinese automaker attempting to establish operations in the US, as car sales are highly regulated. Dealer franchise laws vary by state; new companies must navigate strict rules designed to protect incumbent auto dealers, who are one of the most pro-Trump constituencies in the United States.7 Although it is possible for a Chinese EV maker to acquire an existing dealership network, such as Nissan or Stellantis, as they have done with Volvo, these efforts will likely face severe regulatory scrutiny in the US. (Then again, Trump can be bought (TikTok, crypto) and TACO - Trump Always Chickens Out.)

Chinese EV makers may prioritize markets outside the US, especially given the turmoil and unpredictability caused by Trump’s tariffs. Chinese cars, both internal combustion (ICE) and EVs, are already widely available in Mexico, which now imports more cars from China than from the United States.8 Tens of millions of Americans visit Mexico each year, and they notice attractive, low-cost Chinese electric vehicles, just as they notice low-cost medicine in Canada.

Canada may reconsider its stance on US policy regarding Chinese EVs. During the Biden administration, Canada followed the US lead and imposed 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs to protect its domestic industry, which is closely integrated with the US. Then Donald Trump insulted America’s northern neighbors. He calls Canada the 51st state and slapped pointless tariffs on their lumber, steel, and aluminum exports. Canada is now considering easing its tariffs on Chinese EVs as a way to pressure the US. If attractive, low-cost EVs are available in Canada and Mexico but are blocked in the US, the outcry from US consumers will be substantial.

An Opportunity for American Unions?

Most transplants hate labor unions. They choose to locate in states with Right-to-Work laws that weaken unions financially, and they fight any attempt by their employees to organize. Even heavily unionized German automakers resist attempts to unionize their US factories. Despite decades of effort, the UAW has won only one representation election. On their third try, a substantial majority of workers voted to unionize at Volkswagen’s Chattanooga assembly plant. Since then, the UAW has spent more than a year negotiating its first contract.9

Unbeknownst to most Americans, however, there are already two Chinese-owned transplants in the United States. One is in Ridgeville, South Carolina, where Volvo is actively manufacturing the fully electric EX90 SUV.10 Volvo remains heavily unionized in Sweden, but is no longer a Swedish company. It is owned by Zhejiang Geely Holding Group, a large Chinese EV manufacturer that provides Volvo with substantial financial backing, strategic direction, and access to advanced technology. Volvo leverages Geely platforms and suppliers, such as CATL for battery packs. Recent model Volvos and Polestars are actually Chinese cars manufactured in the US, but they carry Swedish nameplates.

The second Chinese transplant is run by BYD, the company that most frightens US automakers because it has grown so rapidly.

BYD now employs nearly a million people, and more than ten percent of them are R&D engineers. This makes it the largest private-sector employer in China and one of the largest employers globally. Last year, it hired 200,000 people.

In 2024, BYD reported revenue of approximately $100 billion, surpassing Honda and Nissan but still trailing Toyota, General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis (formerly Chrysler). It increased revenue by almost 30% last year by selling 40% more cars.

BYD operates in 88 countries and regions. It has production facilities in Brazil, Hungary, Uzbekistan, and Thailand, with additional factories under construction in Turkey and Brazil. BYD is rapidly expanding in Europe and Latin America. Nearly 90% of its sales were in China, but this year, it outsold Tesla in Europe for the first time (thanks in part to Elon Musk’s rightward lurch). It has set a target for half of its vehicle sales to come from outside China by 2030.

BYD is continuing to cut prices to build market share. Its bestselling Seagull EV now costs less than $8,000, down from $10,700 in 2023. They have cut prices on other models by more than 30%.

Today, BYD is the world’s largest manufacturer of plug-in electric vehicles and the second-largest electric vehicle battery producer. Its super-factory in Zhengzhou is larger than the city of San Francisco and ten times larger than Tesla’s Gigafactory in Nevada.

BYD Lancaster, California. US trade barriers prevent BYD from building cars in the United States; however, the company has been manufacturing electric buses in Lancaster, California, since 2013. The 500,000 square feet plant was built with local political support and incentives, including a $1.45 million package from the City of Lancaster. The plant repurposed a former motorhome manufacturing facility, expanding it to over 500,000 square feet. This expansion enabled BYD to meet the Federal Transit Administration’s “Buy America” requirements by sourcing more than 70% of its components domestically. Today, BYD is the only manufacturer of battery-electric buses in the US and has become the largest in North America in less than a decade.

Astonishingly, workers at BYD Lancaster are represented by a labor union. In 2017, BYD signed a neutrality agreement with the Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers (SMART) Local 105 that pledged non-interference with employee efforts to organize a union. BYD recognized SMART based on a “card check” – essentially a petition by a majority of employees declaring their preference for representation.

The labor agreement led to the establishment of the first electric bus manufacturing apprenticeship program in the US, developed in collaboration with Antelope Valley College and a coalition of community, labor, and environmental groups called Jobs to Move America. The program comprises a six-week pre-apprenticeship and a three-semester apprenticeship, offering workers industry-recognized credentials.

BYD also entered into a Community Benefits Agreement, committing to hire at least 40% of its workforce from veterans, single parents, and individuals who have been formerly incarcerated. This initiative has been supported by nearly $1 million in state funding to develop workforce training programs.

Can BYD Lancaster serve as a model for allowing Chinese EV and battery factories to be built in the US? Donald Trump has declared that the purpose of his tariffs on Chinese imports is to force companies to build factories in the United States. Chinese battery and car makers have expressed interest.

We should acknowledge the obvious at the outset: electric buses are not the same as electric cars. They are purchased by governments that value collegial labor relations. They are presumably higher-margin products and less sensitive to labor costs. They have vastly fewer competitors. They are also small: Lancaster employs 750 people.

The question is, under what terms should the US permit Chinese companies to invest in EV and battery factories? BYD Lancaster illustrates the outline of an interesting social compact: Chinese firms are free to invest in the United States, provided they pay what amounts to a social tax. The US should require:

Good faith bargaining and first contract arbitration in any facility where a majority of workers petition for union representation.

Companies are to enter into training agreements with community colleges and reach community benefit agreements with local communities.11

CFIUS national security reviews to regulate the use of data generated by EVs.

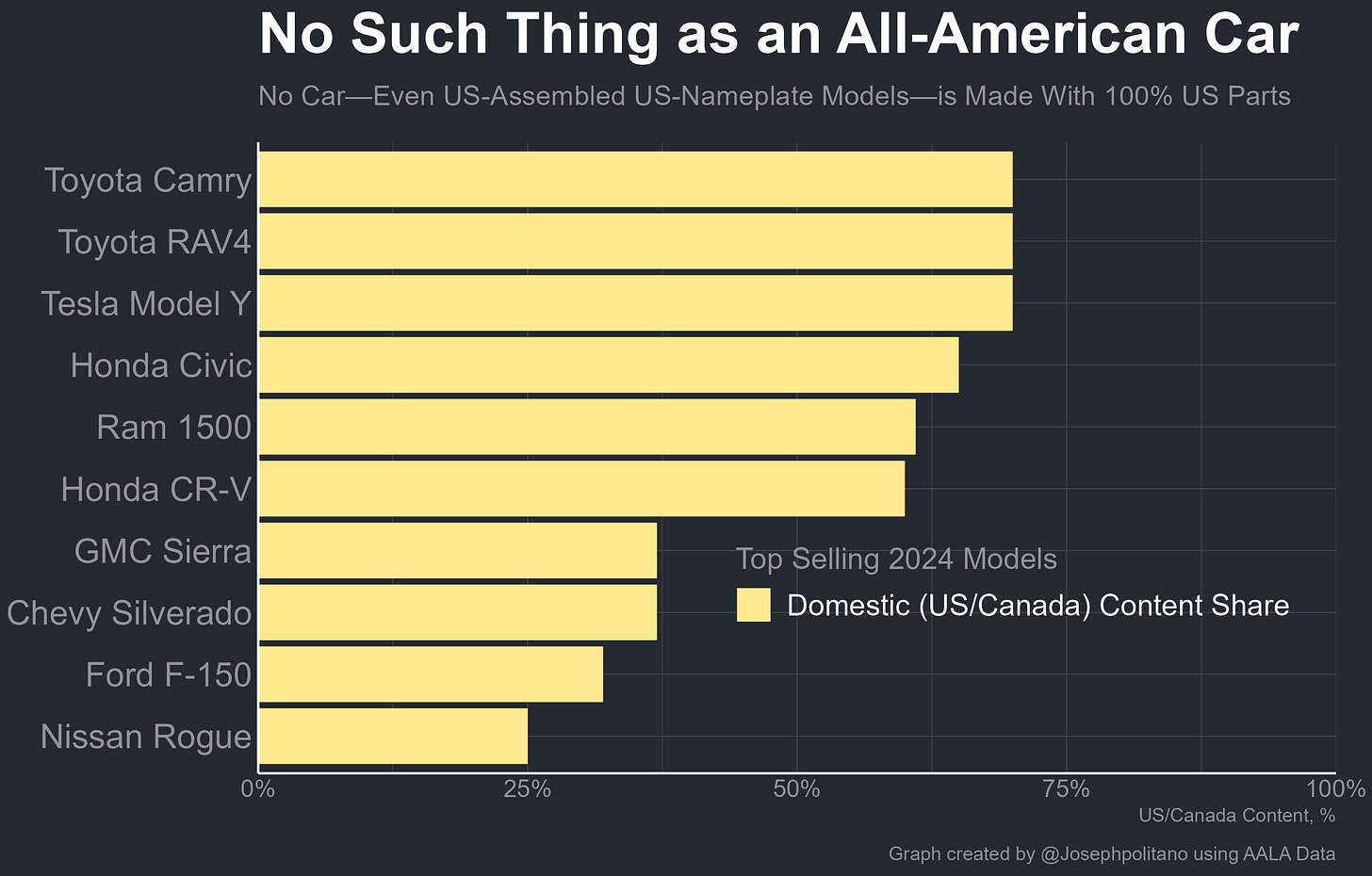

Domestic sourcing of components to strengthen American supply chains. At Lancaster, BYD must use 70% American-made parts. Realistically, however, there are no purely US-made cars.

Source: Joey Politano, Apricitas Economics

Would UAW President Shawn Fein accede to Chinese investment on these terms? If so, is he already holding talks with Chinese EV makers? He would be wise to do so and to focus on unionizing Volvo and Polestar.

Will China Invest?

It is not possible to predict whether or not China will choose to invest under these conditions. But they are already backing BYD and Volvo in the United States. Moreover, recognizing unions, investing in training, and contributing to local communities would help neutralize political opposition to Chinese companies. If Chinese companies commit to this, the US would be foolish to stop them.

Allowing China to invest in US manufacturing will not sit well with legacy US carmakers, who continue to fight the transition to electric vehicles. GM, for example, just announced a pivot away from EVs to its largest investment ever in a new engine factory – nearly a billion dollars for a new V8 engine plant in Buffalo, New York. In an era when electromagnetism is rapidly supplanting combustion as a source of energy, this is madness. A deal with China will also not sit well if it were applied to Tesla and nonunion transplants like Toyota and Hyundai. All are likely to strongly resist any policy that makes it easier for their employees to organize or introduces highly competent competitors.

The debate over whether and how to allow Chinese investment in EV plants will reveal two distinct approaches to industrial policy: stupid and smart. Stupid industrial policy uses tariffs and non-tariff barriers to protect lazy incumbents from competition. This guarantees that American consumers will pay more and get less than consumers in other countries. It is a blueprint for industrial decline.

Smart industrial policy is not designed to shield or subsidize incumbents.

It invests in the research, development, and rollout of industries such as semiconductors, batteries, AI, drones, electric vehicles (EVs), and photovoltaics, which reward first movers, benefit from economies of scale, and drive the emergence of new industries.

It uses small amounts of public capital to attract large amounts of private capital.

It uses tariffs only in a very targeted manner to foster domestic competition, rather than protect incumbents. It expects US companies to export and compete effectively in global markets.

The debate over Chinese auto transplants will reveal which type of industrial policy the United States will adopt. It’s a good time to be smart.

Musical Coda

First, Modern Times will take a break until late June.

Second, some years ago, the extraordinary Tom Lehrer was my math teacher at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He was an astute observer of the Catholic Church. This song has an 11-year-old sense of humor, which is perfect, considering that it was released in 1968, when Pope Leo XIV was 11 years old.

In 1895, Ogden Bolton Jr. designed one of the first battery-powered bicycles featuring a DC hub motor.

There is a surprising amount of journalism and scholarship devoted to exploring how e-bikes led to the development of electric vehicles. See The History of Electric Bikes, The Transition To Electric Bikes In China, China SignPost: Electric Bikes are China's Real Electric Vehicle Story, The Emergence of Electric Bikes in China - Stanford University, The Origins Of The Modern Ebike, From e-bike to car: a study on factors influencing motorization of e-bike users across China, History of electric vehicle industry in China, and The Evolution of Electric Bikes: A Systematic Review of Technological Advancements and Market Adoption.

The NRDC is the direct descendant of the Gosplan-like State Planning Commission. It plays a central role in shaping industrial policy. In 2004, it published the Auto Industry Development Policy, which established the framework for EV development and encouraged the integration of technological standards within the industry. They convened sixteen Chinese state-owned companies to form an electric vehicle industry association in Beijing called CEVA. The goal of the association was to integrate technology standards and develop a best-in-market electric vehicle.

Of course, you want to know. You read footnotes. According to Dick Walker at UC Berkeley, they were the California Motor Car Company (1911-1914), Cole California Car Company (1914-1915+), The California Automobile Company (early 1900s), and the Durant, Star, Willys-Overland (1920s). Also, Chevrolet operated an assembly plant in Oakland starting in 1916.

This is ironic, since China has long insisted that US investments in Chinese factories transfer American technology and know-how to China. Patrick McGee’s outstanding Apple in China details how Apple built a deep, complex, and often uneasy relationship and paid billions of dollars to train Chinese engineers. He demonstrates that Apple is not merely a technology company that manufactures in China; it is a company whose business model, operational strategy, and geopolitical positioning have been profoundly shaped by its entanglements in China. A strongly recommended read.

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an interagency committee of the US government responsible for reviewing the national security implications of foreign investments in US businesses. CFIUS is chaired by the Department of the Treasury and includes representatives from key government departments such as Defense, State, Commerce, and Homeland Security, among others. CFIUS has only blocked eight transactions, with the Qualcomm / Broadcom transaction (2018) being perhaps the best known.

Auto dealers are one of the five most common professions among the top 0.1 percent of American earners. Seth Stephens-Davidowitz found that over 20 percent of car dealerships in the United States have an owner who earns more than $1.5 million per year. Car dealers are organized and donate millions of dollars to local, state, and national politicians. They lobby through NADA, which donates to Republicans at a rate of six to one. Through those efforts, they’ve managed to write and rewrite laws to protect dealers and sponsor sympathetic politicians in all 50 states.

Although EV sales account for only about 2% of total car sales in Mexico, they are increasing by 40% annually. Chinese automakers are offering competitive pricing and taking advantage of local incentives, such as exemptions from driving restrictions on high-pollution days in Mexico City.

The plant also manufactures the S60 sedan and has undergone significant upgrades, including the installation of a state-of-the-art battery pack production line, to support EV manufacturing. In addition to the EX90, the plant also produces the all-electric Polestar 3 SUV, which is built on the same SPA2 platform and shares battery technology with the EX90.

CFIUS reviews can be extensive. The US can require a detailed disclosure of investment sources, ownership structures, board governance, and intellectual property management. It can restrict or firewall sensitive technologies, require data localization, and implement transparent cybersecurity protocols to ensure the protection of sensitive information. It can closely scrutinize investments involving batteries, software platforms, and autonomous vehicle technology.