The Future of Technology Is No Longer American by Default

China is not only flooding markets, they are pulling ahead in nearly every critical technology field.

Advances in technology drive improvements in our living standards. But Americans tend to think about technology as clever, homegrown devices equipped with powerful software. We imagine iPhones, self-driving cars, and ChatGPT. But technology is vastly more than that.

In his terrific new book Breakneck, Dan Wang uses cooking to illustrate three distinct elements of technology.

Tools. The hardware used to complete a task, like pots, pans, and stoves.

Recipes. Codified procedures for using the tools that can be written down and shared, such as blueprints, patents, and written manuals.

Process knowledge. Tacit knowledge or know-how is the practical experience and skills acquired through hands-on work and practice. A novice in a fine kitchen with a detailed recipe cannot produce a great dish without practical experience.

Wang argues that process knowledge is the most valuable part of technology because it is difficult to acquire, document, or transfer. Unlike tools or recipes, it can confer a sustained competitive advantage. He emphasizes the importance of process knowledge in China’s manufacturing success. Wang argues that China’s rise comes not just from invention but from accumulating and refining practical, cumulative expertise in its factories and supply chains. He contrasts this with the biases of Western societies, which often overemphasize tools and recipes, neglecting the critical role of hands-on experience.

The critical importance of diffusing process knowledge can lead companies to cluster geographically, making it easier to share insights with partners and access specialized expertise. The result is industrial ecosystems like Silicon Valley, “Hardware Valley” in Shenzhen, China, or the aggregation of outsourced IT services in Bangalore, India.1

China Now Outperforms the US in New Technology

The uncomfortable reality is that China has now supplanted the United States as the world’s center of emerging technologies. China is the largest global producer of electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, solar modules, advanced robotics, drones, telecommunications and information technology, aerospace equipment, high-speed rail infrastructure, advanced materials, biomedicine, and medical devices.

According to the nonpartisan Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF), China now outperforms the United States across most critical technological fields. They base their conclusions on both leading technical publications and global patents, which tend to predict industrial innovation. China now dominates in both the quantity and quality of peer-reviewed scientific publications across a wide range of fields.

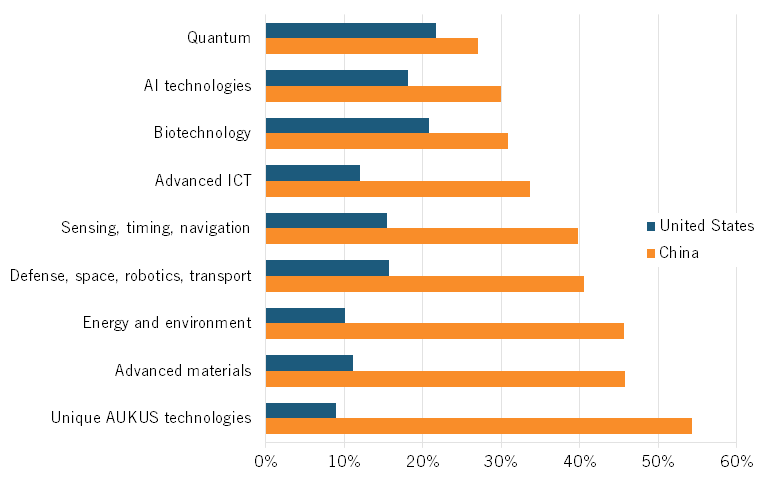

Share of the top ten percent of quality publications across eight critical domains

ITIF’s analysis notes that Chinese state-backed innovation policies, subsidies, and integration across academia, industry, and government have led to a surge in patents. That has real-world consequences: China leads in robotics, batteries, biotech trials, and quantum communication (the 1,200-mile Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) between Beijing and Shanghai is the world’s longest ground-based QKD network). Even in AI, where the US is strong, China is nearly at parity in output.

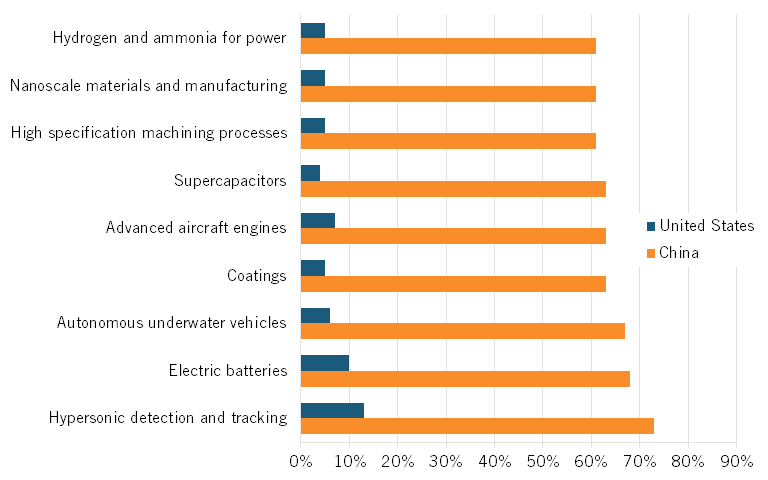

In the scientific subfields where China surpasses the US in research output, ITIF finds that the gap is substantial.

Subfields in which China’s share of the top ten percent of quality publications is more than 50 percentage points greater than the US share

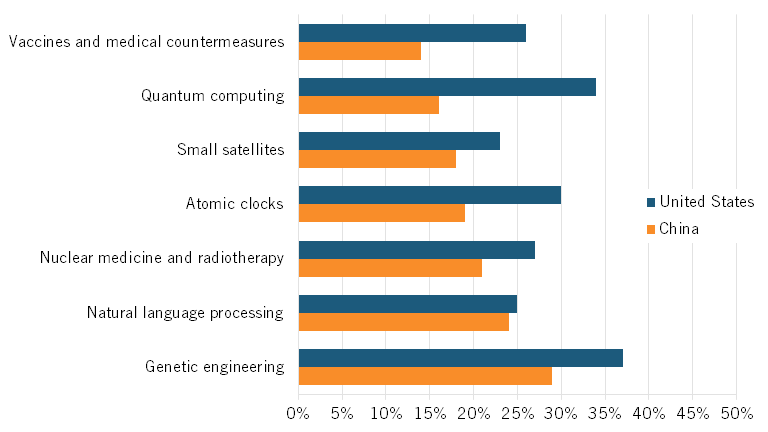

The reverse is not true. Where the US still leads, it is by a lesser margin, and China is rapidly closing the gap.

Subfields in which the US share of the top ten percent of quality publications is greater than China’s share

Another measure comes from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s (ASPI) Critical Technology Tracker. It analyzes 64 critical technologies across eight domains. The scorecard is bracing: China leads in 57 of them; the United States leads in only seven. When examining the top decile of scientific publications, China leads in all eight domains. The gap is most pronounced in energy and environment (46% to America’s 10%). Even in AI, China produces more top-tier work (30% versus the United States’ 18%).

The Long Game

China is no longer playing catch-up; it is now decisively ahead in many critical sectors. The ITIF argues that this is the payoff from decades of investment in education and research. Consider a few examples:

Talent pipelines. Programs like the Thousand Talents Plan attract foreign-trained researchers, particularly in the semiconductor industry, to return to China. As of 2022, over 950,000 foreign professionals contributed to China’s economy, marking a 20% increase from pre-pandemic levels. As the US has erected talent barriers, China has simplified visa processes, offered tax incentives and housing subsidies, and established local integration programs to make relocation easier and more attractive for talented immigrants, 89% of whom were educated in China.

STEM saturation. China now awards more STEM degrees than any other country—over four times the number awarded in the US. China is expected to award double the number of STEM PhDs as the US this year. Even if the median Chinese researcher is not of the same caliber as the median American researcher, in the aggregate, averages lose. Due to its scale, China has more “A students” than the US has students of any sort.

Military-Civil Fusion. The US State Department has noted that state-sponsored research in China has dramatically reduced institutional barriers between the military and civilian sectors. Research flows freely across the two.

The outcome is an accelerating cycle: more talent, more publications, more patents, more geopolitical leverage.

Chinese leadership is evident in far more than just R&D metrics. The Economist notes that China accounts for more than 30% of global manufacturing, surpassing the combined total of the U.S., Germany, Japan, and South Korea.

None of these measures captures the daily experience of Western companies competing with China. They confront a relentless wave of exports that become steadily cheaper and often improve in quality. Because each Chinese province promotes its local champions, competition within China is vicious. Firms are forced to cut costs savagely. Most are desperate to sell abroad, where margins are fatter. The result: China’s export volumes continue to surge. China accounts for one-fifth of global GDP but is now responsible for 36% of all export shipping containers.

Consumers worldwide benefit from China’s overcapacity, but producers outside China pay a heavy price because China’s industrial capacity now exceeds the world’s ability to absorb it. The Economist quotes a foreign executive: “There will come a point in time when China and the world simply cannot absorb more Chinese goods, and I think that point is approaching.”

Unfortunately, Donald Trump is not pressing China to confront their massive overcapacity or to level the playing field for US companies as he attempted to do during his first term. In part, this is because the Chinese tamed Trump by restricting exports of rare-earth minerals and permanent magnets, sending global manufacturers into a panic. Today, Trump directs American negotiators to concentrate on priorities that align with his personal and political interests, including boosting the sales of soybeans and Boeing aircraft, and pursuing an all-American version of TikTok in defiance of a bipartisan law passed by Congress last year. He will be easily appeased.

The US remains the wealthier and more innovative economy on a per capita basis. It remains ahead in entrepreneurial culture, capital markets, and some frontier areas of AI. However, the trend line is unmistakable: China has developed a system that produces scientists, patents, products, and industrial regions at a massive scale.

The future of technology is no longer American by default. Those who believe that scale drives innovation can safely bet on China. Those who value dynamism, openness, and resilience will find that the US still has advantages. Our emerging world appears likely to see the US leading in some high-value niches, while China dominates much of the rest.

Coda

Technologies built on distributed digital infrastructure, such as cloud computing, cryptocurrency, or open-source software, may not rely on geographic clusters; however, many of the fastest-evolving technologies do. I am, of course, indebted to Anno Saxenian, whose research pioneered the study of global technology regions. She has kindly educated me on this topic for four decades.