“Remember, Nobody Reads Anymore”

Taking deep literacy seriously

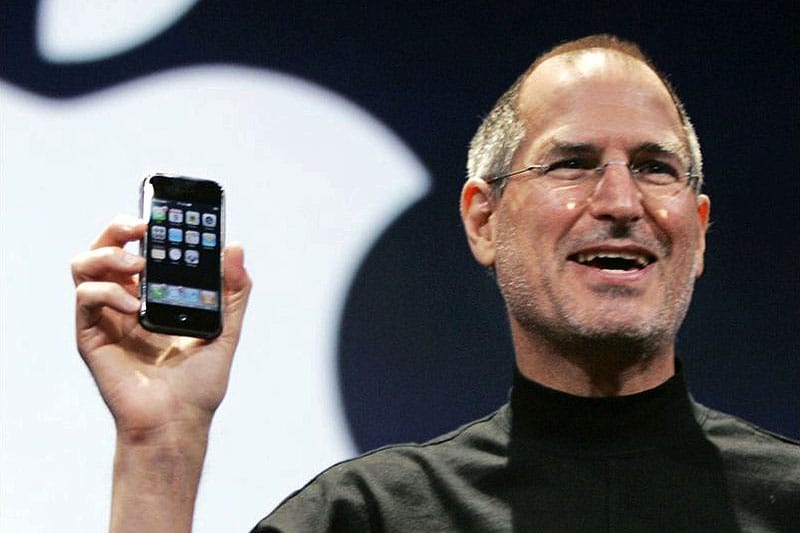

I spoke briefly with Steve Jobs a few times, and the conversations never went well. Whether the topic was workers, walled gardens, or books, he gave the strong impression that I flunked his Bozo test.

Our last exchange was via email in late 2010, about a year before he died. Apple had just launched iBooks along with the iPad. Their new online bookstore was a hot mess, as these things often are at first. I had built an online bookselling company, so I sent him a list of five straightforward ways to improve iBooks. He responded instantly. His reply opened with: “Remember, nobody reads anymore.”

His note told me three things. Apple was not going to challenge Amazon’s emerging Kindle juggernaut and do to books what it had done to music. Pity. Second, iBooks was toast because Steve did not believe in it. And I had once again failed the infamous Bozo test.

Apple still doesn’t care about iBooks. But fifteen years later, “nobody reads anymore” looks prescient, at least concerning deep reading. We “read” social media and romance novels, but fewer of us wrestle with dense arguments, track long chains of reasoning, learn unfamiliar vocabulary in context, and then use that knowledge to think and argue clearly.1

Philosophers from John Stuart Mill to Martha Nussbaum and astronomer Carl Sagan have observed that the ability to engage deeply with complex texts is a cornerstone of individual and social development. It is difficult to develop critical thinking, sustained empathy, or democratic participation without it. Without deep literacy, our media values vibes over verification, our political values become unanchored, our workplaces struggle to train talent, and our institutions fail more often at collective problem-solving. The excellent Brink Lindsey compares the American decline in deep literacy to the “Brain Drain” that can occur between countries.

National data on reading achievement, adult skills, and how people spend their time highlight a real deterioration in deep-reading culture. We cannot address cultural or social phenomena like this directly, but we can take steps to encourage deep literacy and improve our collective ability to think.

Reading Less. Thinking Less. Doing Less.

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) surveys large numbers of students in fourth, eighth, and twelfth grade. It is often called the Nation’s Report Card. On the NAEP long-term trend assessment, 13-year-olds’ average reading scores fell again in 2022–23—down four points from 2019–20 and down seven points from a decade ago. On NAEP’s scale, this is a sizable drop, especially on the back of long-running stagnation.

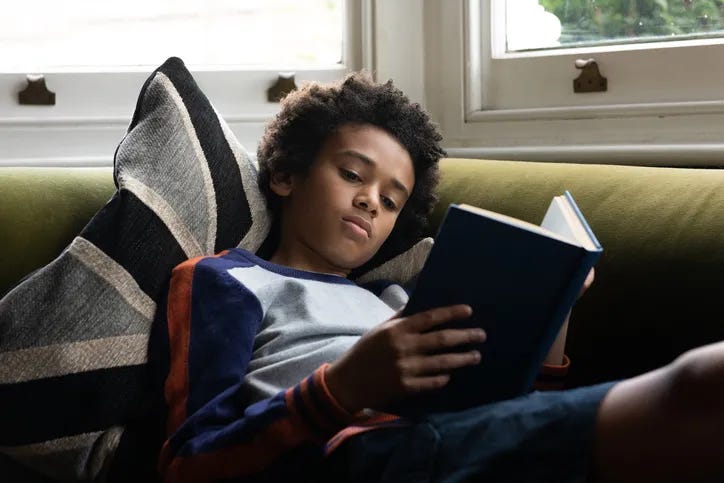

The American Time Use Survey (ATUS) reveals how we spend our time. In 2023, only 14% of 13-year-olds said they read for fun “almost every day,” the lowest share ever recorded, down from 27% in 2012. If deep literacy is a muscle you build through repetition and difficulty, America isn’t exercising as much as it once did.

Adult data tell a similar story. On the OECD’s international PIAAC exam, U.S. adults score around the OECD average in literacy and below average in numeracy and technology-rich problem-solving. That’s tolerable for those satisfied with being average — but it’s unnerving for those who think the world’s scientific and financial superpower should be better than middling at reading and reasoning.

Poverty amplifies every social problem from crime to health, education, and housing. Persistent poverty means that millions of families are denied safety and security, and dignity in the most prosperous large country in the world. It is therefore no surprise that higher literacy and higher earnings are correlated. Economist Jonathan Rothwell finds that adults who read at a sixth-grade level earn nearly twice as much as those reading below a third-grade level.

Phones don’t help. Device ubiquity is now nearly total: roughly 95% of teens have access to a smartphone; the share who say they are online “almost constantly” has roughly doubled since 2014–15. The ATUS shows teenagers reading for ~9 minutes per day on average, while spending more than an hour a day on games or computer use for leisure. Older Americans (especially women) still read; the young don’t.

Attention is finite. Over time, we become what we do. When young people spend less time doing deep reading and more time scrolling, we should expect gaps in deep reading skills to get bigger.

The Deep Literacy Flywheel

Reading is a flywheel: slow to start, but powerful and able to deliver compounding returns once it’s spinning. Lose momentum and you not only lose compounding returns, but it’s hard to restart.

The political scientist Adam Garfinkle describes how the deep literacy flywheel works. He sees readers doing the mental work of anticipating an argument, interrogating it, and integrating it with what they already know about vocabulary and background knowledge. This, in turn, enables comprehension of still more complex texts.

This isn’t just a problem for students in humanities classes. Vocabulary growth from reading translates into better comprehension across subjects; prose comprehension is a binding constraint on math word problems, science labs, workplace training manuals, legal compliance, and civic information. Print, as several decades of psycholinguistics attest, exposes you to rarer words than speech and social media. It accelerates vocabulary growth and background knowledge – the raw materials of thinking.

A nation that reads less will, on average, think less well about hard things—budget math, environmental trade-offs, biomedicine, geopolitics. It contributes to brittle politics and conspiracy-friendly discourse.

Is this just misplaced nostalgia or moral panic about “kids these days”? After all, moral panics, especially about children, are now something of a fashion industry. Children and teens are becoming more depressed, less conscientious, and less social. We used to worry about kids drinking and having sex. Now we worry that they don’t. After all, we often overlook how skills migrate from paper to pixels and how new literacies emerge as others decline.

We should keep those caveats in mind. But the NAEP and ATUS series are long-running and methodologically serious – and they point in the same direction. The better argument is not whether a deep-reading slump exists—it does—but what steps we might take to arrest and reverse it.

Culprits and Cures

Several forces apply the brakes to the deep literacy flywheel.

Poverty. The correlation between family income and literacy is strong, positive, and well-documented. The well-off enjoy a virtuous cycle: higher‑income families tend to raise children with stronger reading skills, which in turn helps them earn more later in life. Kids raised in poverty face another vicious cycle. They fall behind early and stay behind.

Phones. Screens have colonized what used to be dead time for books—bus rides, bedrooms, boring afternoons. “Almost constant” connectivity is now the default setting for teens, parents, and, ahem, old folks. Many of us feel that long-form reading carries a huge opportunity cost.

School. Many classrooms replaced whole novels with short passages engineered to teach “main idea” and “finding evidence.” It shows up in vocabulary, the gateway drug to comprehension. Students mainly acquire it through print, not chat. Finally, “the science of reading” rightly re-centered phonics and decoding texts, but made no effort to build systematic knowledge across subjects. We declared victory at “Johnny can read”, not “Johnny can analyze arguments.”

Commodified attention. Social media is strongly biased toward spectacle. A media diet of two-minute clips, dunks, and vibes is a training plan for superficiality.

No government can mandate deep literacy. At best, we can help cultivate it. Evidence suggests that parents, schools, publishers, platforms, and policymakers can nudge readers in a more productive direction.

Tutor pre-K and elementary students. Professional and academic research both find that high-dosage, one-on-one or small group tutoring during school significantly improves reading results, especially among students from lower-income households. Volunteers and “service year tutors” who have graduated from high school can make these efforts financially workable. As, potentially, can AI-tutors.

Teach content, not just “reading skills”. Assigning and discussing content-rich books in history, literature, and science helps build literacy. Use texts to teach knowledge, vocabulary, and stamina.

Measure and track results. What gets measured, gets done – so schools need to track and report time spent reading, vocabulary growth, and content knowledge across grades.

Compelling content. With teens whose reading minutes are close to zero, this effort is more like cardiac rehab than varsity training. It requires irresistible content (sports bios, true crime, celebrity memoirs, entrepreneurial how-to, military history, graphic nonfiction). In Sweden, making the content compelling mattered more than banning mobile phones (although Swedish classrooms already make greater use of laptops than other schools, so this finding may not replicate elsewhere).

Add friction to social media. We need to regulate social media, not to censor it, but to add friction. Schools, carriers, or Apple can issue devices set to focus modes by default. They can batch notifications, disable infinite scrolling, and time-limit apps. If platforms can gamify streaks for snaps, they can gamify streaks for chapters.

The issue here is emphatically not whether the median American reads Proust. It is what share of Americans can grasp three thousand words on zoning, Ukraine, or GLP-1s and come away with the gist, the caveats, and better questions than the ones they started with. We should care whether training materials lead to fewer workplace injuries, whether new hires can master the documentation for the tools they’ll use, and whether voters can tolerate arguments that don’t fit on a bumper sticker.

We like to believe that America’s strength is its ability to learn and adapt. But learning and adapting require sustained attention, delayed gratification, and humility in the face of complexity. Our attention economy sells the opposite. Our internal brain drain is not a flight of people, but a flight from the practices that make people smarter over time.

If we want abundance—in innovation, in productivity, in social trust—we need citizens who can sit with complex texts and difficult problems. We need to take reading – and thinking – much more seriously.

Musical Coda

Publishing is not dead. Romance and erotic fiction are top-performing genres by revenue. Science fiction and Romantasy are also strong, along with graphic novels, comics, and Manga. Long-form nonfiction growth is strongest in health and well-being, diversity and inclusion, and narrative-style storytelling.

Great article Marty! It's so true that 240 characters is not enough for coherent discourse.