As AI Gets Better at Thinking, We Are Getting Worse

Why Post-Literate May Be Neo-Feudal

When I was in high school, information was scarce, so people who had more of it were seen as smarter. Then a teacher surprised me by declaring that intelligence wasn't just about collecting information, but “the ability to reason and to learn.” His idea that reasoning and learning are skills I could improve with practice changed how I viewed education. It might be the most valuable lesson I learned in high school.

Today, nobody worries about accumulating information. We carry humanity’s store of it in our pockets. But our ability to reason and learn has become demonstrably worse.

The Attention Recession

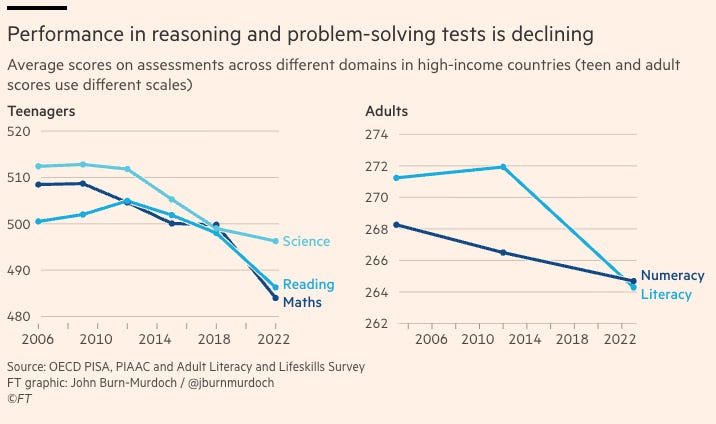

Since about 2012 — just as smartphones hit critical mass and social media conquered our attention spans — our performance on tests of reasoning and problem-solving has steadily declined. Not just in America. Not just among teenagers. Everywhere and across all age groups.1

The OECD's PISA scores, which measure 15-year-olds' performance in reading, math, and science across many countries, reached their peak in the early 2010s. They have been declining ever since. The pandemic didn't help, but scores dropped more sharply between 2012 and 2018 than during the chaos of Covid.

Adult literacy and numeracy skills are declining rapidly. A staggering 35% of American adults struggle with basic mathematical reasoning. They cannot "review and evaluate the validity of statements" using math. As AI masters mathematics, one-third of the citizens in the most educated society in human history cannot verify the accuracy of their grocery store receipt.

This is an "attention recession"—except instead of shrinking GDP growth, it’s our collective ability to focus, reason, and solve new problems that is diminishing. And unlike economic recessions, our shift to a post-literate society has been happening for over a decade, with little public notice or action.

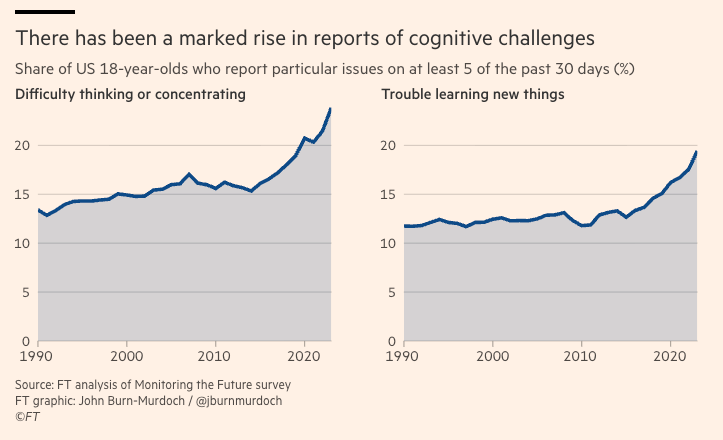

Since the 1980s, researchers have been asking 18-year-olds: Do you have trouble thinking, concentrating, or learning new things? For thirty years, the answer stayed quite steady at about 15%. Then, around 2015, it started to increase. That was when infinite scroll became the main way people consumed information. It’s when we stopped choosing what to read and began letting algorithms decide for us.

In 2015, researchers found that the average American was already checking their phone 46 times per day. Today, it’s over 200 times each day. By 2015, we were spending almost six hours each day interacting with computer or phone screens. Now, it’s over seven hours daily, and for younger people, it's nine hours.

The big shift isn't from books to screens—it's from active to passive consumption. From intentional browsing to algorithmic feeding. From finite web pages to endless, never-ending streams of content that update every time you blink. This is new. As recently as 2010, we would have actively navigated to a trusted site, perhaps CNN or Time Magazine, to read or skim an article of interest. We might have deliberately clicked on a link to a related site.

Today, a young person opens TikTok and is immediately bombarded with a dozen or more very short videos about cooking hacks, political outrage, and dancing pets. Nobody intentionally chooses this content, which disappears before the user can even form a coherent thought about any of it. These sites reshape how we consume information, creating a neurological pattern similar to a slot machine. Like a lab rat, we pull to refresh, enjoy the dopamine rush, and repeat. It’s reminiscent of soma, the docility-enhancing drug mandated by the state in Huxley’s Brave New World, but without the resulting sex or solidarity.2

Think Different?

This marks a significant historical reversal. Thanks to Gutenberg’s printing press, by the mid-1700s, many people started to read. The result was an unprecedented transfer of knowledge to ordinary men and women. Literacy brought a different way of thinking. Oral, tribal, and highly emotional thinking habits that had supported feudalism gave way to informed debates. Once literacy rates reached about fifty percent, people in America, England, France, and Russia stopped listening to kings and overthrew feudal systems. Over time, something more like democracy replaced it.3

Before the badly-named “smartphone,” the rise of the internet promised an equally profound revolution. With information and education freely accessible, a golden age of human reasoning was expected to follow. Instead, we have created its opposite: smartphones have replaced reading with emotional and irrational forms of communication and thinking that resemble the fear-filled tribalism rejected by our ancestors.

It is unlikely that we can sustain the operations of history’s most complex civilization with a population increasingly addicted to feudal ways of thinking and communicating. Nothing presents a greater challenge to our culture and democratic politics.

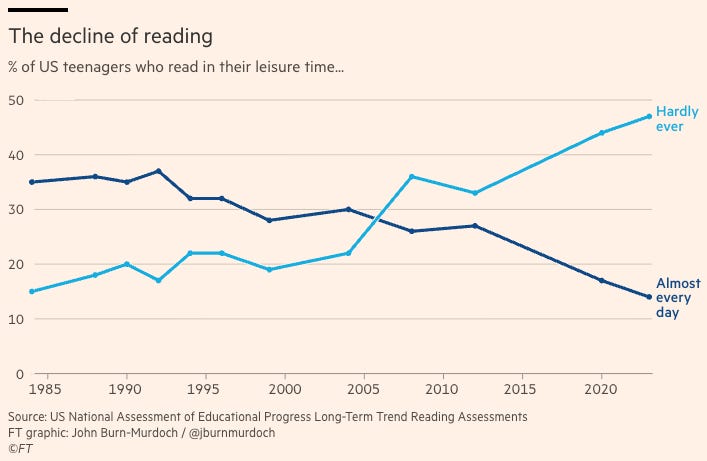

The data on reading starkly illustrate the problem. By 2022, AI tools were starting to analyze every word ever written. That year, for the first time, most Americans did not read a single book. Even nations with strong reading traditions are seeing a decline in mathematical and scientific reasoning. This points to something more significant than "kids don't read anymore."

In an attempt to address information shortages, we developed tools that unintentionally exacerbated cognitive problems. We have more information than ever, but we're less capable of using it to make logical, factual decisions. We have access to more free educational content than many of history’s great scholars could have imagined, yet we still struggle with basic logic.

The issue is not digital technology, which research shows can enhance cognitive performance. When users select what to learn and engage with, screens can serve as powerful tools for reasoning and problem-solving. But that's not how most of us use technology.

Part of the problem is frequent context-switching. Forcing our brains to constantly toggle between brief feeds targeted at us, notifications, and alerts isn't just annoying; it actually damages our working memory, our ability to handle complex information, and our capacity for self-regulation. We've handed over our attention to algorithms that are designed not to educate, but to capture.

The result is a form of learned helplessness—we've become so used to being fed information that we've forgotten how to seek it out ourselves. If social media were a drug, it would be classified as a Schedule 2 narcotic like cocaine, which has a high potential for abuse, even if it also has accepted medical uses.

Now What?

The great dumbing down is a deliberate choice, not an unavoidable fate. Humans designed and built the technology that causes our attention to decline. We haven't suffered a collective lobotomy – the human brain hasn't changed in the past decade. Our reasoning, creative, and problem-solving capabilities remain intact. What has changed is the environment we're asking our brains to operate in. We have created systems that make us worse at thinking. We can also develop systems that enhance our performance instead of diminishing it.

The first step is to recognize a serious problem. The second is to understand that individual willpower isn't enough. We need structural changes to how we consume information and how companies deliver it. Will this require us to confront powerful companies that sell our attention to outrage entrepreneurs and deny responsibility for the consequences? Of course it will.

Five reforms would provide a solid foundation.

Name and shame addictive apps. Lists vary, but the top ten apps based on hours of use include YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, Snapchat, Telegram, Threads, and X (nee Twitter). These addictive sites should carry warning labels like cigarettes do.

Ban anonymous and automated social media accounts. Too much online abuse and misinformation hide behind nameless profiles. Requiring real identities fosters responsibility. About 15% of social media accounts are bots that distort debates, spread propaganda, and fuel scams. Reserve social media for real people with names. Activists and whistleblowers who benefit from anonymity don’t need to rely on social media.

Tax social media. We tax polluters to recover the social costs they impose. Ideally, the taxes cover the cost of cleanup. As evidence grows that social media imposes costs without paying for them, we should tax them like any other negative externality.

Ban phones in schools. For good reason, most schools now restrict smartphones. They have found that smartphones hinder learning, attention, and social development. Teachers and students are realizing that a school day without constant distractions and comparisons boosts education and mental health.

End Section 230 immunity for algorithmically promoted content. Platforms that choose what to amplify are effectively publishing content. This makes them liable under current law for the harms their algorithms spread, just like book publishers are liable for any harmful content or libelous disinformation they print. There is no compelling reason to exempt social media platforms from liability for the content they promote.

My high school teacher was right: intelligence is a human ability that we can either degrade or improve. We do this by creating technology that challenges us to be smarter and more human. Right now, we're not passing that test.

Coda

George Harrison, Jeff Lynne, Tom Petty, and Bob Dylan pay a quick tribute to their missing Wilbury, Roy Orbison, at 1:46.

John Burn-Murdoch of the Financial Times uncovers more interesting data and social trends than any journalist writing today. The charts here are from his excellent article Have Humans Passed Peak Brain Power?

In Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman famously observed that “What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book because there would be no one who wanted to read one.”

James Marriott’s Substack post, The Dawn of the Post-Literate Society is an excellent essay on the social impact of declining literacy, with splendid anecdotes about the central role reading played in the lives of Teddy Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, David Bowie, and Paul McCartney. He opens his essay with the Neil Postman quote referenced above.

Very good, though I'd add something. Changing one's mind, or for that matter learning almost anything, involves realizing you were wrong. This can happen learning math, and it can happen in debate. It can happen in reading. Unfortunately, we now have a media ecosystem that rewards people in their mistaken beliefs by introducing them to lame supporting arguments and the triumphant vehemence of other wrong people. There's less incentive to appreciate the infinite value of realizing you are wrong.

Could not agree more. The tax idea is excellent. Also one of the best songs from one of the best groups ever.