The Drug That Cures Everything

Are GLP Meds a Modern Miracle? Or is God Trolling Us?

Two years ago, I convinced a physician to prescribe tirzepatide to help me lose weight. Also known as Mounjaro or Zepbound, this is a GLP-1 drug like Ozempic. I told the story here. (Reminder: I still have no clinical qualifications, and this is still not medical advice.)

GLP drugs have been around for twenty years. Researchers have uncovered massive side benefits as these drugs have improved and become widely used. In addition to treating diabetes and obesity, GLP drugs appear to reduce the odds of stroke, heart disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, alcoholism, and drug addiction. Some days, GLP meds look like the drug that cures everything. Or is God trolling us with false hopes?

GLP medications work in three different ways. Initially, they were valuable because they modulate glucose levels by naturally increasing insulin. This is helpful if you are diabetic. We then realized that GLP meds reduce appetite by influencing the brain's digestive system and dopamine circuits. This can lead to fantastic weight loss and possibly treat a variety of addictions. It now turns out that GLP meds may also reduce chronic, low-level inflammation that contributes to various unpleasant diseases. If these findings hold up, GLP medicines will be among history's most valuable and widely used. If not, they will be among the most hyped.

Let’s take a closer look.

Diabetes

We often know that a drug works without understanding how. Felix Hoffman invented aspirin at Bayer in 1897. It was a useful pain-reliever and became very popular. But we did not understand how it worked until 1971, when a British pharmacologist discovered that aspirin reduces inflammation, pain, and fever by suppressing prostaglandins.

We understand how GLP meds prevent or treat diabetes. When we eat, our intestines produce a hormone called GLP-1 (Glucagon Like Peptide-1, here shortened to GLP). GLP signals the pancreas to produce insulin, which reduces the spike in blood sugar caused by eating.

Ozempic and its kin are fake GLPs (you cannot just administer real human GLP because it breaks down immediately). Scientists searched for proteins that imitate GLP, so-called mimetics or agonists. The discovery that Gila monster venom is a natural incretin mimetic helped researchers to slowly figure out how to bind GLP to a common blood protein. This research took decades, but would be much faster today thanks to the exploding power of generative AI in biological research.

Obesity

As with aspirin, we knew that GLP meds helped people lose weight before we understood exactly how they did it. At one level, it seems obvious. A drug that makes your body think you have just eaten leads you to eat less.

But GLP is doing more than regulating insulin levels. It slows down the rate of “gastric emptying”, so food stays in the stomach longer and suppresses feelings of hunger. It affects the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that controls hunger. It interferes with dopamine production – the feel-good hormone that rewards eating. It appears to have a direct effect on fat, making the body more likely to break it down.

For many years, scientists debated whether GLP mainly affected the body or the brain. Using rats with GLP receptors removed from their brains or their bodies, they worked out the answer: it’s mostly the brain.

This was surprising. Scientists thought that the blood-brain barrier blocked large-molecule drugs from touching the brain. They are still trying to figure out how GLP molecules get through. Scott Alexander summarizes the technical details of current thinking in a fine article here.

A sudden treatment for obesity is fantastic because obesity is one of history’s most important and difficult public health challenges. About forty percent of Americans are obese and about six percent now use GLP medications. Another six percent have used them in the past.

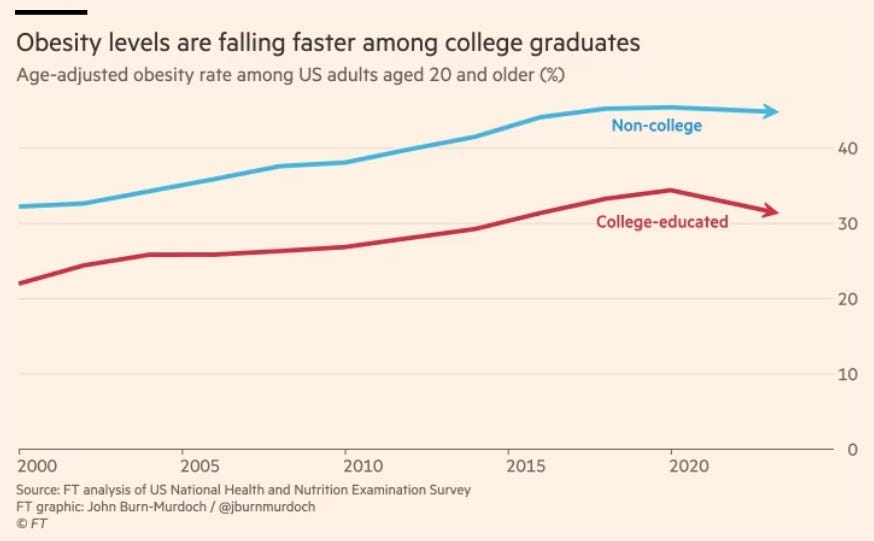

It appears to be making a difference. Obesity rates have risen in every country in the world and had never fallen in any of them. But data from exams gathered between 2021 and 2023 suggest that obesity may have dropped in the US last year.

Was this change due to GLP medications or something else? We don’t know for sure, but there is at least one indication that it was the drugs. John Burn-Murdoch at the Financial Times noticed that obesity peaked first among college graduates, the group most likely to adopt new medications.

Addiction, Including Alcoholism

With the drug's surge in popularity, doctors and patients began to notice yet another striking side effect. GLP drugs reduce many people's cravings for alcohol and other addictive substances. When I began using GLP meds, I immediately lost my appetite for alcohol and coffee. The drugs hold promise for treating addiction to alcohol, tobacco, stimulants, and opioids. They may even help with behavioral addictions like porn, gambling, shopping, and shoplifting.

Many pharmacologists who study GLP meds are not surprised. Elisabet Jerlhag and her colleagues at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden research how GLP drugs reduce alcohol consumption in rats. They have published multiple studies showing that the meds inhibit binge drinking in rats or mice and prevent relapse in "addicted" animals. Animal studies suggest that GLP drugs reduce the consumption of nicotine, opioids, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

GLP drugs reduce addictions not by regulating insulin, but by interrupting dopamine cycles. Addictive drugs nearly always trigger dopamine. Dopamine in the striatum (the brain's motivation center) signals all sorts of behavior – not just eating. GLP drugs appear to reduce the release of dopamine in this region. The result is that you have less appetite for addictive substances that trigger dopamine. Fortunately and somewhat strangely, GLP meds do not reduce less destructive forms of pleasure like exercise, enjoying music, having sex, playing with your kids, or watching sports.

Can GLP meds actually be used to treat drug addiction effectively? Probably — but the research is in still progress. (To track news about GLP drugs and addiction, follow the excellent Recursive Adaptation Substack.)

Dementia, Including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s

People who suffer from diabetes are at much higher risk of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other forms of dementia. As a result, anything that prevents diabetes reduces dementia.

However, GLP drugs prevent dementia in non-diabetics, so something more is going on. The most likely explanation is that the meds reduce inflammation. Inflammation is much more destructive than researchers appreciated a generation ago. Inflammation is a helpful immune response to an infection, but random microbes in the air and food, stress, poor diet, and lack of exercise can trigger low-grade, persistent, and toxic inflammation. GLP drugs seem to stop some of the inflammation most implicated in dementia.

Does this make sense? Why would an appetite-related hormone affect inflammation? How exactly does it work? There is some specialized, promising research in this area, but we don’t yet have full answers.

Stroke, Heart Disease, Kidney Disease, and Obesity-related Cancers

Now we are getting ridiculous. A single class of drugs that can treat diabetes, cause life-changing weight loss, cure addictions, and prevent dementia is already hard to believe. Now we are being told that GLPs prevent stroke, heart disease, kidney disease and obesity related cancers? Really? Can it make me look young again too?

Two things are going on here. First, inflammation is multifaceted and broadly damaging. Aspirin or ibuprofen sometimes helps. We suspect that GLP medications suppress inflammation in distinct ways, but we don’t yet know for sure. Preliminary evidence that GLP meds reduce cardiac and kidney disease, and obesity-related cancers are still based on observational research, not controlled trials. Most are still speculative, even if they are plausible.

Second, bringing new drugs to market is so expensive that pharmaceutical companies have an unhelpful incentive to discover new uses for any approved drug. Pfizer developed sildenafil to treat high blood pressure and angina. Along with some of their male subjects, they were thrilled to discover that sildenafil had a side effect: it induced erections. Pfizer brought the drug to market as Viagra. It is still prescribed occasionally for pulmonary hypertension, but it became one of the best-selling drugs of all time as a treatment for erectile dysfunction thanks to a side effect.

If drug companies discover that GLP drugs have positive side effects, these drugs will become even more spectacularly valuable and subject to even greater research. Unfortunately, this incentive does not always improve the quality of the scientific research needed to resolve these questions. Nor does it help excited researchers stay focused. The history of pharmacology is littered with promising drugs that induced researchers to report the results they were hoping to find. GLP meds have so many people so excited that we are already seeing unhealthy hype.

Scott Alexander summarized the hype tendency well:

Everything works through GLP-1! GLP-1 makes the sun shine! GLP-1 makes the grass grow! Nobody knows what caused the Big Bang, but cosmologists are increasingly convinced that GLP-1 might have been involved! You should come back in ten years and check which of these claims have survived. My guess is very few.Hollywood adds to the hype, as usual. But not all of the fuss about GLP meds is drug company or social media propaganda. We see too many effects of GLP meds on improvements in addiction and heart disease that are independent of obesity and endocrinology. Something else is going on. Even if these observations do not lead to treatments, God is not trolling us. We should welcome the massive investment in research that these drugs are receiving.

Diet and exercise will always be step one for controlling blood sugar, reducing inflammation, and battling addiction. But they are often not enough. GLPs seem likely join the growing list of drugs and vaccines designed to prevent as much illness as they treat. As generative AI radically accelerates our understanding and discovery of new preventative medicines, we should brace for more breakthroughs — and prepare for more hype.