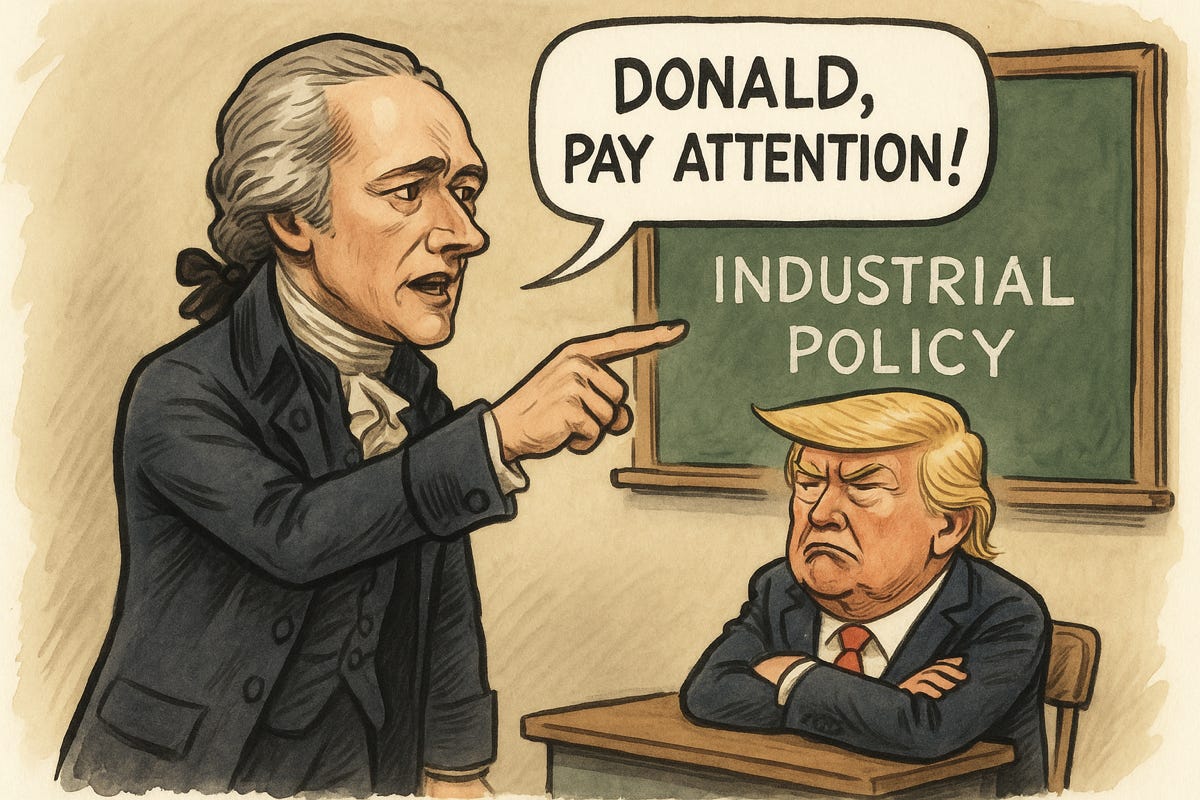

Donald Trump is No Alexander Hamilton

Without an Industrial Strategy, Tariffs are Theater

In the earliest days of the United States, Alexander Hamilton spotted a big problem. The young republic had earned its political independence, but it was economically as dependent as any colony. To Europe, America was a source of cotton, tobacco, and timber, as well as a market for its ships, textiles, and tools. Hamilton understood that, left to market forces, America would be reduced to supplying commodities to Europe and dependent on European exports. He knew that an economically dependent nation would not be politically independent for long.

So Hamilton proposed America’s first industrial policy. He called for tariffs to protect infant industries, government investment in infrastructure, and a federal role in steering economic development. In his foundational 1791 report to Congress On Manufactures, he laid out a vision for a muscular, ambitious government that would help push the fledgling US economy up the value chain.1

Over the strong objection of southern plantation owners, Hamilton argued that the nation must do more than extract and export crops, timber, or mineral resources from its abundant land. Hamilton insisted that America participate in the complex and valuable work taking place at the technological frontier. America needed to not only harvest crops, but build harvesting machines. It needed to refine the metals it mined into railroads, warships, and factories that could make America wealthy.

Thanks to Hamilton, America laid the groundwork for an industrial economy long before the Industrial Revolution arrived. Hamilton’s vision inspired a generation of economic nationalists, including Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, and Abraham Lincoln, who championed tariffs, industrial initiatives, and public investment.

Donald Trump claims to be part of this legacy. He embraces the rhetoric of industrial greatness. He imposes tariffs and talks about bringing manufacturing home. But he is borrowing one of Hamilton’s tools while completely misreading the blueprint. His tariffs are Hamiltonian cosplay that reveal a deep misunderstanding of history.2

Hamilton Moved America Up the Value Chain. Trump is Moving Us Down.

Hamilton and his successors focused on building the canals, railroads, naval power, and later telegraphs and land grant colleges that enabled private investment and innovation. Trump’s industrial policy is based on cultural grievances, not on a plan to promote advanced industries. He protects steel and aluminum companies that employ fewer than one-tenth of one percent of the U.S. workforce by imposing downstream costs on sectors like cars and aerospace, which employ millions of Americans.

According to a 2019 Brookings Institution study, Trump’s steel tariffs raised prices for U.S. manufacturers while having minimal impact on employment in protected industries.

The Peterson Institute found that the 2018 steel tariffs cost American companies about $900,000 for every steel job “saved”. This is not Hamiltonian industrial policy—it’s economic triage for sectors that Trump favors because they employ men in hard hats. It would have been far cheaper to just pay steel and aluminum companies $50,000 per worker to not lay them off.

Trump appears not to grasp the complexity of modern value chains. In Hamilton’s time, the value chain for a wool coat was linear: a farmer grew and sheared sheep. He sold it to a mill that spun thread and wove cloth. The mill sold wool cloth to a tailor who took measurements and sewed a coat. Today’s manufacturing value chains are not linear; they are more like a neural network. Multiple iPad and iPhone models are assembled in China from parts that come from dozens of overseas countries and hundreds of Chinese suppliers. Subassemblies may cross borders multiple times. Even “Made in America” often means “Assembled in America with parts from everywhere.”

Modern industrial policy recognizes this complexity. Its goal is not to create simple factory jobs, but to position a nation at the most complex nodes of this global web: discovery, design, engineering, software, and advanced manufacturing and materials. As MIT economist David Autor puts it, countries climb the value ladder by “specializing in complexity, not just production.”

Contra Hamilton, Trump is subsidizing commodity activities like mining and smelting over high-complexity discovery, design, and assembly. His recent decision to impose tariffs on copper no doubt pleases mining companies in the swing state of Arizona, but it punishes companies that rely on copper to make electric vehicles, wind turbines, and data centers.

Trump understands that copper matters. His announcement on Truth Social correctly acknowledged that copper “is necessary for Semiconductors, Aircraft, Ships, Ammunition, Data Centers, Lithium-ion Batteries, Radar Systems, Missile Defense Systems, and even, Hypersonic Weapons, of which we are building many.” Given this goal, why would we impose tariffs on copper and much else that raise costs for these industries? Why protect low-value work and punish the complex manufacturing that creates most of the economic value, adds to our national security, and generates the best jobs?

Hamilton Promoted Immigration and Investment

Hamilton did not focus just on tariffs – his goal was to develop skilled people and investment capital in growth industries. As Dartmouth economic historian Douglas Irwin has shown, America’s explosive 19th-century industrial boom happened because of immigration and investment, not tariffs alone. By 1900, nearly 15% of the U.S. population was foreign-born, helping fuel the labor demands of an expanding industrial economy.

Trump, by contrast, is assembling a large private army to enforce some of the harshest immigration restrictions in modern American history. He aims to shrink the inflow of both low-skilled and high-skilled workers, even though the United States has long depended on brains and muscle from around the world, just as we once relied on Irish and Chinese workers to build railroads.

Hamilton took steps to encourage private investment in infrastructure and education, which Trump has made more difficult. Trump’s signature economic policy is his 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which Congress recently renewed. The TCJA cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, in the hope that companies would invest the taxes they saved in higher wages and higher-growth industries.

That didn’t happen. A 2020 National Bureau of Economic Research study found that corporate investment increased only modestly after the tax cut and primarily funded investment plans that predated the TCJA.

Companies passed their tax savings to shareholders. Instead, companies used the tax break to buy back shares and increase dividends. In 2018, buybacks reached $583.4 billion, a 52.6% increase from 2017, while capital investment rose only modestly. The average dividend paid by corporations increased by 10.8% following the tax cut, which did much more to boost shareholder returns than it did to promote investment in public education or infrastructure.3

Companies increased pay — at the top. Wage increases after the TCJA were highly concentrated at the top. Careful research at Yale University concluded that “Workers’ earnings gains are concentrated in executive pay and in the top 10% of the within-firm income distribution, while workers in the bottom 90% of the distribution see no change in earnings.”

Conservatives have a predictable response: it’s fine for companies to return cash to owners because they will invest their windfall in more productive businesses. It is not easy to track reinvestment, but there’s no compelling evidence that investors redeployed their TCJA gains into more productive enterprises. Instead, it appears that investors recycled their wealth mainly within the financial system rather than reinvesting it in the real economy.

Investors banked their gains or parked them in existing financial instruments. Following the FCJA, asset prices rose, but capital formation did not. For example, venture capital and startup funding did not grow in proportion to the buyback surge. Investment in high-growth, innovative sectors like clean energy or AI rose later in the 2020s, not immediately following the TCJA. There was no surge in entrepreneurial activity or capital investment tied directly to the tax cuts. Instead, high-income individuals (who hold most stocks) appear to have saved their windfalls in passive funds or low-yielding financial assets, not in riskier or more productive ventures.

The productivity data does not suggest that capital moved to more efficient uses. Total factor productivity growth (a rough proxy for innovation and efficient capital allocation) remained sluggish after the TCJA. According to the Congressional Budget Office, GDP growth spiked temporarily in 2018 but returned to pre-TCJA trends by 2019.

TL;dr: Tariffs and Tax Cuts Are Tools, Not Strategies

Tariffs and tax cuts have always been useful tools in a nation’s economic arsenal. Hamilton and Lincoln used tariffs as part of a system that tied tariff protection to investment, innovation, infrastructure, and immigration. Kennedy and Johnson cut taxes as part of a Keynesian recession recovery plan. To quote a recent NYT op-ed, “tariffs belong in our trade arsenal — but as precision munitions, not as land mines that maim foes, friends and noncombatants equally.”

Trump’s grievances and nostalgia for America’s industrial past are no substitute for well-considered strategic goals. He has long treated tariffs like a magic wand — an all-purpose symbol of toughness divorced from any coherent theory of how American industry actually wins. Without a strategy, his policies will sabotage the complexity-based manufacturing future that America needs.

Trump is right to steal Hamilton’s ideas, but he needs to steal all of them. We need not only well-targeted tariffs, we need Hamilton’s ambition, focus on investment, openness to talent, and willingness to adapt.

Coda

Or, as Lin-Manuel Miranda memorably put it in his rap bio of Hamilton:

“How do you not get it?

If we’re aggressive and competitive,

The union gets a boost,

You’d rather give it a sedative?”

Trump's irresoluteness, his tendency to impose tariffs, back off, then impose them again, has led investors to openly debate various TACO Trades – meaning ways to profit from bets that Trump Always Chickens Out.

The TCJA also made it more expensive for states and local governments to finance infrastructure three ways. It raised the cost of municipal bonds because it reduced the value of their tax-exempt status. This raised borrowing costs and discouraged new infrastructure projects. It limited the deductibility of state and local taxes (SALT), further increasing the cost of property taxes, making voters less willing to approve new infrastructure spending. And the higher deficits that resulted from the tax cuts mean America has less fiscal space for investments in infrastructure, education, and technology in the future.

Who among the Demcratic leadership is prepared to make these arguments? Are the Democrats still trapped in their own protectionist heritage fueled by Labor's desired to protect jobs?