Congress is Frozen in Time. Let's Thaw it Out.

The case for modernizing The People's House

On the final day of the Constitutional Convention, after intense debate regarding the size of the House of Representatives, Convention President George Washington took the floor at Independence Hall.

In a pivotal speech, Washington backed Nathaniel Gorham’s motion to empower Congress to expand the House as the population grew. He argued that a larger House would bolster “the security of the rights and the interests of the people”. His speech swayed the remaining founding fathers. With Washington’s backing, Gorham’s motion passed unanimously.

As a result, Congress grew steadily for more than a century. We started with 65 representatives. After each census, Congress added seats: 105, 142, 182, and so on. In 1912, we reached 435. Then, after the 1920 census, Congress froze itself. It refused to reapportion at all, largely because rural interests didn’t like what urbanization would do to their clout. In 1929, instead of fixing the problem, Congress set the House at 435 seats and let a formula reallocate them among the states after each census.

As a result, the average House district has now more than tripled in size, from ~210,000 people per district after the 1910 census to ~761,000 after the 2020 census. Trump’s plot to reapportion seats before the census in Texas and elsewhere sidesteps the larger debate about how best to make Congress more democratic.

America still has the same 435 seats it had during the Gilded Age. This distorts representation, magnifies the Electoral College’s small-state bias, and leaves many voters functionally voiceless.

This is not normal. Other advanced democracies periodically adjust the size of their lower houses as populations grow. We don’t. The UK has about 100,000 people per Member of Parliament, and German Bundestag members represent about 116,000 members each. The Pew Research Center found that eight OECD countries have larger lower chambers than the U.S. House, even though most have far smaller populations. Our representation ratio is among the worst in the democratic world.

Moreover, those 435 seats are increasingly locked inside gerrymandered single-member districts where most elections are a formality. At the moment, we are arguing about how and when to redistrict states, but the larger problem for those who want a representative Congress is that we have too few representatives, and we elect them the wrong way.

The fix isn’t mysterious. The New York Times editorial board identified the problem a few years ago and laid out two reforms that have since been debated and refined. To restore American democracy to “one person one vote”, we need to expand the House and replace single-member districts with multi-member districts elected by ranked-choice voting.

Bigger Districts Mean Worse Representation

Colossal districts change the basic job description of a member of Congress.

Constituent service becomes triage. Handling veterans’ benefits or Social Security cases at scale is harder when one office is responsible for three-quarters of a million people.

Retail politics becomes impossible. You can “know” a town of 30,000. You cannot really know a district of 760,000, let alone one approaching a million people (as in some fast-growing states).

Campaign costs soar. A congressional campaign in a huge media market is a seven- or eight-figure exercise. That tilts power toward large donors and party committees and away from insurgent or community-rooted candidates.

The people who get lost first in this system are not the loudest partisans; they’re the cross-pressured voters who don’t line up neatly with either party’s online persona. They’re also often racial and ethnic minorities in fast-growing metros whose numbers are big enough to deserve multiple seats but not big enough to dominate a single oversized district.

Shrink the districts by enlarging the House, and a few things happen right away. First, Representatives have fewer people to serve and can plausibly know more of them. Second, grassroots campaigns become feasible once again. Campaigns can rely more on door-knocking, town halls, and local media instead of wall-to-wall TV and social-media blitzes. Finally, in many places, additional seats would allow minority communities or distinct regions to elect someone of their choice, rather than being subsumed into a single mega-district.

Political scientists sometimes rely on the cube-root rule: the size of a country’s lower house should be about the cube root of its population. For the U.S. in 2020, that works out to around 690–700 seats. It’s not a crazy benchmark. A House in the 650–750 range would still be smaller than Germany’s relative to population, but it would be in the same ballpark as other advanced democracies.

That’s the representational logic for a bigger House. There’s also a presidential one.

The Electoral College is built directly on top of the House because each state gets a number of electors equal to its House seats, plus two for its senators. When you freeze the House at 435 while the population grows and shifts, those two “Senate electors” loom larger for small states. Today, 100 of 535 electors are the result of having 50 states. Expanding the House reduces the Senate bonus and makes the Electoral College more proportional to population.

Analyses by reform groups and political scientists show that enlarging the House would not automatically favor one party forever; it would depend on where growth is happening. But it would reliably shrink the gap between the national popular vote and the Electoral College outcome and increase the relative influence of voters in large states whose current under-representation is most severe.

If you think of the Electoral College as a flawed but entrenched institution, expanding the House is one of the few levers that makes it less distorting without requiring a constitutional amendment.

The standard objections to enlarging the House (“Where Would Everyone Sit?”) are almost charmingly small-bore.

Physical space. The current House chamber is designed for 435 desks, but that’s not a constitutional constraint. Many legislatures (including the British House of Commons) don’t have seats for every member and rely on benches, rotation, and digital tools. Committees—not floor debates—are where most substantive legislative work happens anyway.

Cost. Adding, say, 200 members would mean salaries, staff, and office space. But even a generously staffed expansion would amount to a rounding error in a federal budget measured in trillions. We are not talking about a new aircraft carrier; we’re talking about making it possible for your representative to have fewer than a million constituents.

Complexity. A bigger House would be messier. Good. The Founders didn’t design Congress to be elegant; they designed it to be representative and argumentative. If anything, the current House is too streamlined and disciplined by party leadership. Adding more voices, especially if they are elected from more diverse districts, would distribute power downwards.

Still, there’s a limit to what House expansion alone can do. If we keep electing those extra members in winner-take-all single-member districts, we will still live in a gerrymandered country, albeit one with more lines on the map.

That’s where the second important reform comes in.

End Gerrymandering With Multi-Member Districts and Ranked-Choice Voting

In our single-member district system, gerrymandering is not a bug; it’s a feature. When each district elects exactly one winner, the party drawing the lines has a strong incentive to pack the other party’s voters into a few safe seats and crack the rest across many slightly-leaning districts. Even in states like California, which outlawed the most grotesque maps (at least until recently), the underlying incentive never disappears. The solution is to stop assuming each district must elect exactly one member.

Reformers around FairVote and others have pushed the Fair Representation Act, which would pair a larger House with multi-member districts elected by ranked-choice voting. The structure looks like this:

Instead of 12 single-member districts in a state, you might have 3 districts that each elect 4 members.

Voters rank candidates in order of preference. Many states and cities have introduced rank-choice voting (aka “instant runoff”). It works well.

Seats are allocated proportionally: roughly every 20–25 percent of the vote in a 4-member district should translate into one seat.

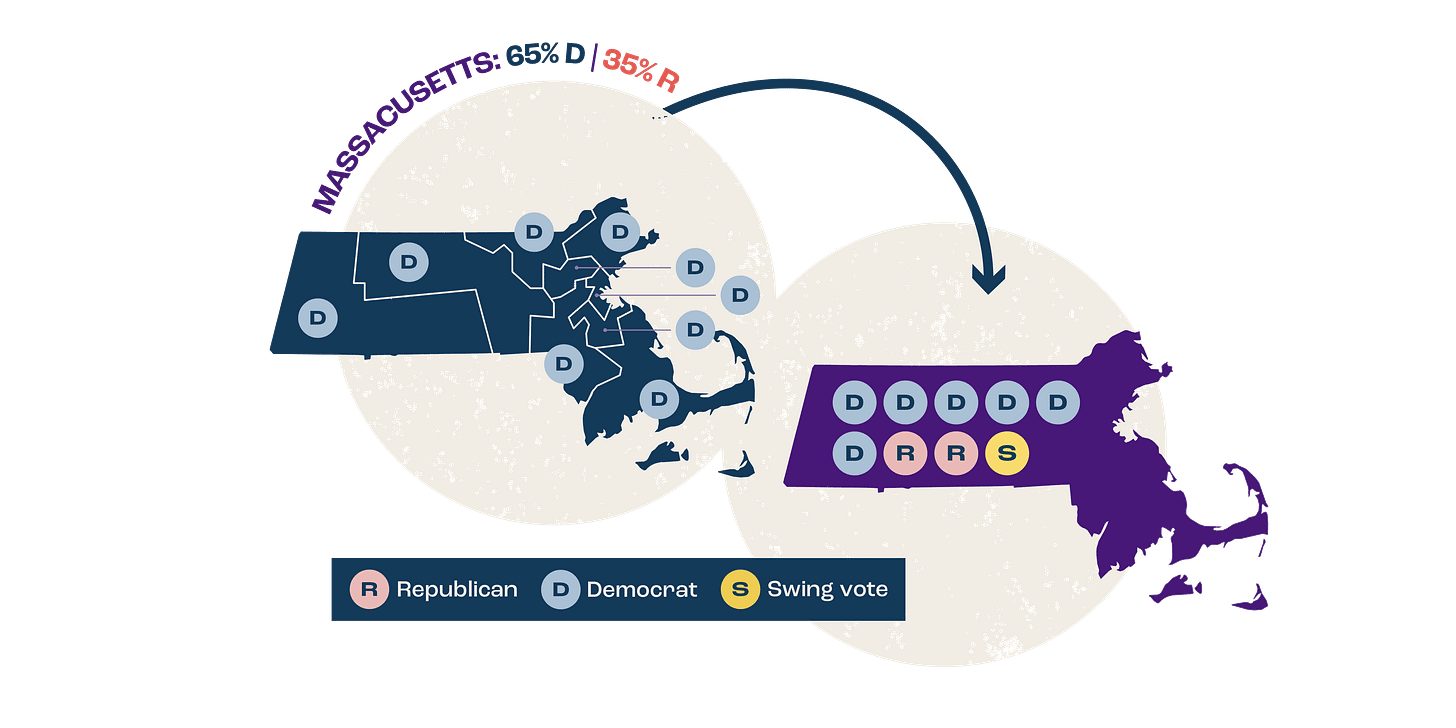

Here is how it might affect Massachusetts (whose 1813 Governor Elbridge Gerry created a district shaped like a salamander and gave us the term “gerrymandering”).

Under that system, a state that is 60–40 in partisan terms doesn’t get a 12–0 congressional delegation. It probably gets something like 7–5. And both parties have strong incentives to run candidates who appeal to second-choice voters as well as their base.

Mathematically, multi-member districts with ranked-choice voting are much harder to gerrymander into absurdity. A research team at Cornell, modeling these systems, found that multi-member districts “blunt” gerrymandering’s impact and produce much fairer seat-to-vote ratios than single-member maps, even when one party controls line-drawing. Even better: use a commission of retired judges to draw the lines, as California did until recently. In a democracy, you want voters to choose their representatives, not the other way around.

Best to Combine the Two Reforms

You could expand the House without changing how we elect it, or you could adopt multi-member districts without expanding the House. But doing both produces the biggest gains.

Districts get smaller geographically and numerically. A metro area that currently has one sprawling seat might have two or three, combined into a multi-member district.

Representation becomes more proportional. Parties that win 40 percent of the vote in a district consistently win about 40 percent of the seats there, instead of getting shut out.

Primary extremism loses some of its grip. In a safe single-member seat, the only race that really matters is the dominant party’s primary, which often has low turnout and is highly ideological. In a multi-member, ranked-choice district, there are no primaries. Candidates have to think about how to be acceptable second- or third-choice candidates to a broad electorate.

Communities of interest can elect someone. Urban suburbs, rural regions, and minority communities that are now sliced and diced to serve statewide partisan goals would have a better chance of electing at least one representative who actually speaks for them.

No Amendment Required

Crucially, none of this requires a constitutional amendment. Congress can change the size of the House by ordinary statute, as it has repeatedly done in the past. It can replace single-member, winner-take-all districts with multi-member, ranked-choice districts. The barrier is political will, not legal architecture.

The case for enlarging the House and moving to multi-member districts is not a technocratic tweak. It’s about whether the basic structure of American democracy matches the country it’s supposed to represent. Right now, it doesn’t:

We have a population of 330 million represented by a House sized for a country of 92 million.

We have districts so large that “representation” is a statistical abstraction rather than a lived relationship.

We have an Electoral College whose distortions are amplified by a needlessly small House.

We have a single-member district system that practically begs politicians to choose their voters instead of the other way around.

A bigger House moves us back toward the Founders’ expectation that the “People’s House” would keep expanding as the country grew. Multi-member, ranked-choice elections move us toward a system where votes translate into seats in a way that feels intuitively fair—and where every voter, in every part of the country, has a real chance to help elect someone.

It would be noisier. It would be more crowded. It would be slower to manage and harder to whip into lockstep. We might need to enlarge the Capitol. But the People’s House would look a lot more like the country itself.