Affective Polarization Makes Us Paranoid

But Quiet Compromises Happen Routinely Outside of Washington

There’s an interesting paradox in American politics right now. We’re allegedly more divided than ever, but when you look at the data, it shows that Americans are seriously mistaken about what their political opponents actually believe.

Consider this striking statistic from 2020: Dartmouth’s Polarization Research Lab found that members of each party believed support for political violence from the other side was four times higher than it actually was. Democrats’ true support for political violence measured about 10 on a 100-point scale, but Republicans thought it was around 40. Similarly, Republicans' actual support was also low, but Democrats estimated theirs at 40 as well.

More recent data confirms this pattern: fewer than 4% of Americans support political violence as of 2024, yet we continue to believe our opponents are either the French 75 or the Christmas Adventurers Club, as depicted in Paul Thomas Anderson’s excellent new film One Battle After Another.1

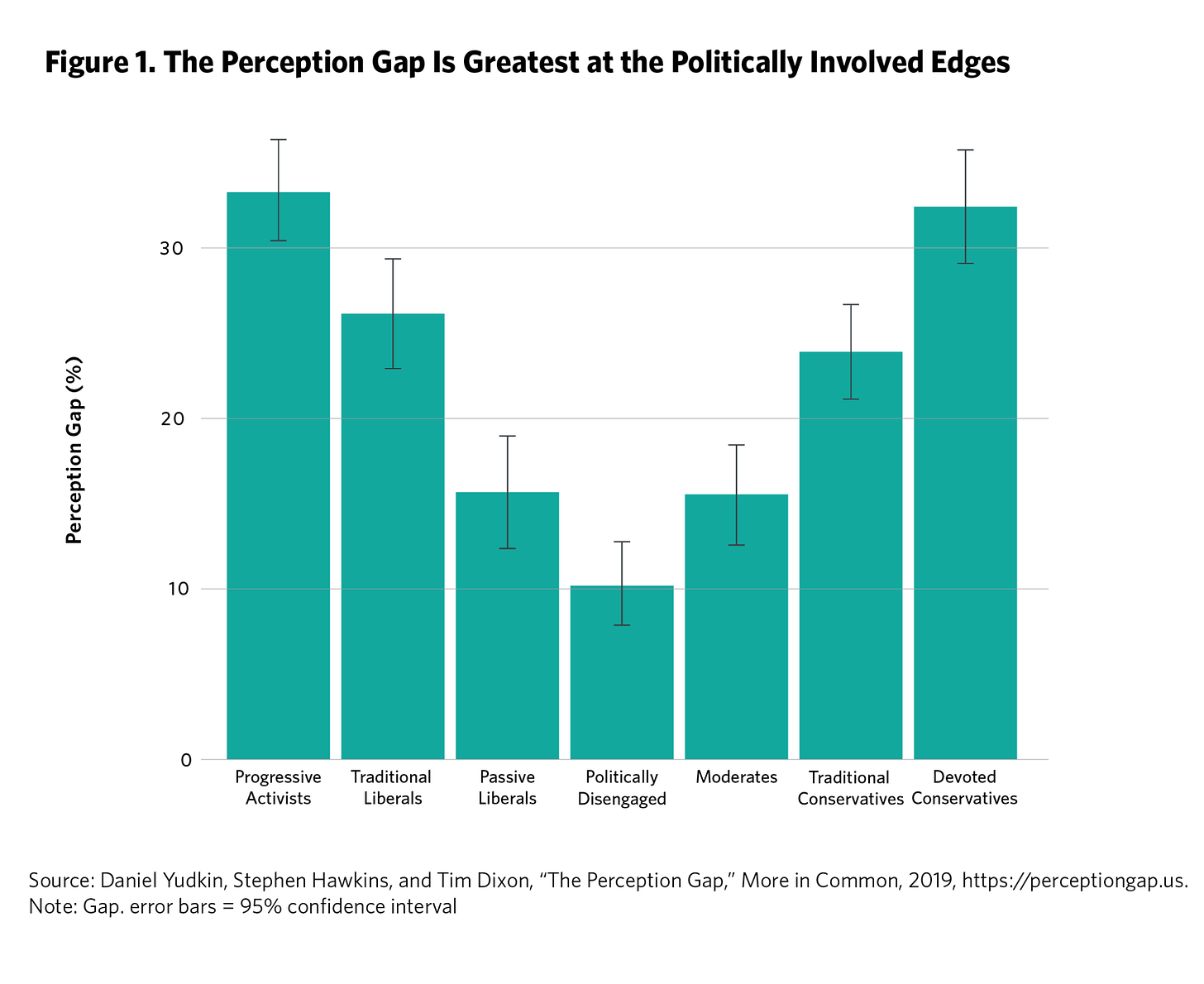

Political scientists refer to this phenomenon as “affective polarization.” It’s less about policy disagreements and more about viewing opponents as fundamentally flawed people. It has become much worse, especially among those who are politically active. Activists and elected leaders are two to three times more likely to misperceive their opponents than those who are less engaged. The people who most need to communicate and compromise are the least able to do so.

The Big Sort: How We Lost Our Messy Coalitions

To understand why this happened, remember how American politics used to work. Not long ago, the main debates focused on economics (tax and spending policies) and the Soviet threat. These were policy disputes with clear middle grounds. If one side wanted $100 billion in spending and the other wanted none, they could negotiate to $50 billion. Even Cold War hawks like Nixon and Reagan found ways to deal with Moscow or Beijing. The country’s political leadership included both conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans.

But as these issues faded, a fundamental shift occurred. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, both parties ignored deficits and adopted similar “borrow and spend” fiscal policies, despite their rhetoric. New divisions arose around cultural and social issues like abortion, gay rights, immigration, and religious liberty, which were deeply felt and seemed to leave fewer clear compromises.

In his book Why We Are Polarized, Ezra Klein explains how the parties experienced what he calls “the big sort.” Decades ago, both parties were large, diverse coalitions. There were pro-life Democrats and pro-choice Republicans. You had deportation hawks and amnesty supporters in both parties. The tents were so big that party affiliation didn’t predict your stance on every topic. In fact, the main criticism of the parties was that they were too similar – a complaint you don’t hear often today.

Today’s parties are heavily sorted by ideology. Thirty-seven percent of Americans describe their political views as “very conservative” or “conservative,” 34% as “moderate,” and 25% as “very liberal” or “liberal”. The key change is that these ideological identities now align almost perfectly with party membership.

When a party predicts ideology, cultural identity, and social group, politics begins to feel existential. Each side doesn’t just see the other as wrong on policy — they view them as an alien tribe threatening their way of life. This makes us terrible at understanding what the other person really thinks. Studies consistently show that Americans overestimate how extreme the other party’s positions are, overestimate how much the other side dislikes us, underestimate areas where we could find common ground, and assume the loudest voices represent the median voter.

Political leaders on both sides have learned to capitalize on this. In the toxic aftermath of the horrifying murder of Charlie Kirk, Vice President JD Vance claimed that more people on the left than on the right support political violence.

Polls differ on this question, but the facts about who commits political violence do not. Multiple studies show that right-wingers have carried out many more acts of violence in recent years. The right-leaning Cato Institute finds that political violence is rare but more likely to come from right-wing than left-wing activists. A 2024 Justice Department study reached the same conclusion, although for some reason, the DOJ has recently removed this research from its website.

Compromise Is Happening Anyway

Despite the noise and glorification of “uncompromising” populists on both the left and the right, Americans are quietly finding ways to compromise on these so-called “impossible” cultural issues.

Abortion. With Roe overturned, states have negotiated a range of approaches instead of simply choosing between total bans and no restrictions. Voters in seven states approved ballot questions protecting abortion rights during the 2024 elections. Still, even in conservative states, the laws often include nuanced provisions concerning gestational limits, parental consent, and medical exceptions.

Gay Rights. Acceptance of gay rights has grown even among conservative circles where it was once completely taboo. The shift has been remarkably rapid and bipartisan at the grassroots level.

Homeless encampments. Democratic mayors in progressive cities have started to adopt more conservative views about clearing homeless encampments. San Francisco, hardly a conservative stronghold, has implemented new restrictions on homeless encampments — demonstrating that even on highly charged cultural issues, pragmatic compromises can be reached.

Immigration. Immigration provides perhaps the clearest example. There’s now a broader consensus across party lines that the asylum system is broken and needs reform. Most Americans agree that the ideal number of immigrants to the United States must be finite and recognize that mass deportations of long-term residents are both cruel and economically disastrous. The ability of states to make compromises is another reason to leave some of our immigration visas to the discretion of states.

This is how federalism is meant to work. We are a nation of 340 million people with genuinely different values and priorities. The founders created a system that could accommodate this diversity through the trials and errors of individual states. That’s why Justice Louis Brandeis famously called states our “laboratories of democracy.”

The irony is that while Washington becomes more gridlocked and social media amplifies the most extreme voices, state and local governments are actually achieving partial victories, half-measures, and brokered compromises because they have to — they can’t just tweet angrily and raise money off the division they create. Political issues may have become nationalized, but political progress remains local.

Why This Isn’t Obvious

The incentive structure in Washington favors performative outrage over practical problem-solving. As a result, it’s difficult for an elected official in Washington to admit to messy compromises, even in their own state. Acknowledging that compromise is possible invites a reaction from their base, criticism from donors (who are often more polarized than voters), and social media backlash. However, there is quiet progress: day by day, state by state, Americans are doing the hard work of democracy — finding ways to live together despite differences, even when our national politics suggest we’re heading toward civil conflict.

The data shows that we’re less divided than we believe, and more able to compromise than our politicians admit. That’s a solid foundation for democracy, even if it doesn’t go viral on social media or make for exciting cable news.

Coda

The movie is funny, nicely shot, and exceptionally well-acted, but it drags in places. At 2 hours, 50 minutes, it’s at least half an hour too long.