Venturing in the Slipstream: the Magic of Astral Weeks

We are re-living 1968 culturally and politically, so let's review a long-overlooked album released that year.

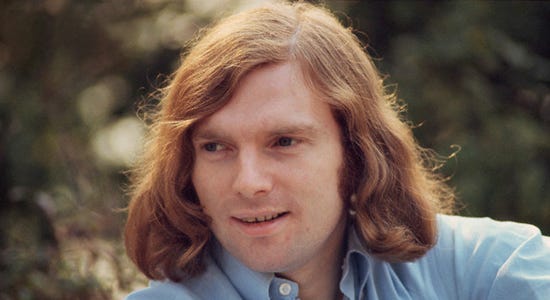

Sometimes an artist captures lightning in a bottle. Usually, they aren’t sure how it happened; few can repeat the magic. In 1968, Van Morrison recorded Astral Weeks under awful circumstances. Today, it is widely recognized as a transcendent work, one of the greatest albums ever recorded. It has made me feel alive for five decades.

The story behind Astral Weeks is as remarkable as the album itself.

1967 ended badly for Morrison. He was 22, in New York, and broke despite the commercial success of “Gloria” (which Van wrote when he was 17) and “Brown Eyed Girl”. He had creative differences with Bert Berns, owner of Bang Records, who’d brought Van to the US after his band Them broke up. Berns had signed Van to a dodgy contract and produced Morrison’s hit single Brown Eyed Girl.

On December 30, Berns died of a sudden heart attack, and control of Bang passed to his vindictive wife Illene. She banned Van Morrison from her studios, continued to block royalty payments, threatened any club tempted to offer him a gig, and asked authorities to deport him when she discovered that her husband had not filed all of Van’s immigration paperwork.

Then she handed Van Morrison’t contract to a mobster friend named Carmine (Wassel) DeNoia. According to Ryan Walsh, author of Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968:

One night, Morrison, whose immigration status was tenuous at best, got into a drunken argument with DeNoia, who ended the conversation by smashing an acoustic guitar over the singer’s head. Morrison promptly married his American girlfriend, Janet Rigsbee (a.k.a. Janet Planet), and escaped to Boston.

Hiding out in Cambridge, Van went acoustic. One night Lewis Merenstein, a Warner Brothers executive, heard him play a song called Astral Weeks. “I started crying. It just vibrated in my soul, and I knew that I wanted to work with that sound” Merenstein reported years later.

Warner Brothers set to work figuring out how to resolve Morrison’s byzantine contractual problems (one part of the resolution required Van to record 3 songs each month for three years for Bang. He did all 36 songs in an afternoon. They were original, discordant nonsense. The contract did not stipulate that the songs had to be good).

As producer, Merenstein decided to back Morrison with jazz musicians. He contacted Richard Davis, who had performed with Sarah Vaughan and Oscar Peterson. They found guitarist Jay Berliner, who had recorded with Harry Belafonte and Charles Mingus.

This was musically a brilliant decision, but the chemistry was tough. Jazz musicians collaborate — but the irascible Belfast Cowboy didn’t. He strummed his songs, skulked back to his isolation booth, and told the musicians to “follow him and stay out of the way”. There were no preparation meetings, no discussions about different approaches, and no lead sheets – the basic thematics of a song that give musicians something to improvise from. Ultimately, the musicians appreciated this artistic freedom, even though Van stayed in his recording booth and never spoke to them. They found the young Irishman not just shy, but anti-social.

After three sessions in September and October of 1968, Merenstein took the tapes to a studio and dubbed strings into some songs. Predictably, Morrison hated results. “They ruined it,” he said later. “They added strings. I didn’t want the strings. And they sent it to me, it was all changed. That’s not Astral Weeks.”

Years later, Van recalled the times:

“You have to understand something,…A lot of this … there was no choice. I was totally broke. So I didn’t have time to sit around pondering or thinking all this through. It was just done on a basic pure survival level. I did what I had to do.”

Warner issued Astral Weeks in November 1968. They did not promote the album, and it failed commercially. One prominent industry critic compared Morrison to Jose Feliciano. According to Merenstein:

“(Warner Brothers) just didn’t know what to do with it so they did nothing. They were expecting ‘Brown Eyed Girl’, and the first thing I played them was a seven-minute song about rebirth with no electric guitars and an acoustic bass. They just shook their heads.”

Astral Weeks never even reached the Billboard 200. But eleven years after it came out, it got an extraordinary review by Lester Bangs. When Rolling Stone reviewed the album for a second time in 1987, it pronounced Astral Weeks a hidden masterpiece. Almost two decades after its release, they declared that the album:

“sounded like nothing else in the pop-music world of 1968: soft, reflective, hypnotic, haunted by the ghosts of old blues singers and ancient Celts and performed by a group of extraordinary jazz musicians, it sounds like the work of a singer and songwriter who is, as Morrison sings in the title track, ‘nothing but a stranger in this world.’”

The album sold slowly but acquired a solid following. It took 35 years to sell its millionth copy and “go gold”. Many Van Morrison fans don’t know the album and many who know Astral Weeks are not fans of Moondance, Domino, and Wild Night.

Astral Weeks profoundly affects people. I discovered it in the seventies when I was the same age Morrison was when he wrote the music. Producer Merenstein said in 2009, “To this day it gives me pain to hear it. Pain is the wrong word—I’m so moved by it.”

The album has been compared to an impressionist painting – it evokes without directly portraying. It’s poetic, even mystical, with syncopated rhythms, frenzied and painful vocals, and lyrics that evoke images instead of ideas or stories. In many respects, Astral Weeks is vocal jazz without the customary extended solos and improv. Some find loose or hidden narratives in the music, which Morrison describes as largely stream-of-consciousness fit to a melody.

Morrison wrote all of the songs on the album in 1966-67 when he was 21 or 22. He told the LA Times that Astral Weeks is “poetry and mythical musings channeled from my imagination.” And quite an imagination it was:

Astral Weeks, the brilliant opener, described by Morrison as “one of those songs where you can see the light at the end of the tunnel.” The Warner guys were right — this ain’t “Brown-Eyed Girl”.

Beside You in contrast, is “..basically a love song. It’s just a song about being spiritually beside somebody.”

Sweet Thing is a popular, circular lyric about nature and romance, described by one critic as “seemingly beginning in the middle of a thought: ‘And I will stroll the merry way.’” The song title became a term of endearment in popular culture.

Cyprus Avenue refers to a street in Belfast described by a local as “where all the expensive houses and all the good-looking totty came from…mostly upper-crusty totty…There’s a couple of big girls’ grammar schools up ’round that direction.” The song is over the top with longing and harpsichords.

Clinton Heylin described The Way Young Lovers Do as a “lounge-jazz” sound that “still sticks out like Spumante at a champagne buffet.” It may be the only track that would get a B.

Madame George was originally titled “Madame Joy” and Morrison sings the words “Madame Joy” in the song. A swirling, compassionate song about a transvestite (or about George Ivan Morrison?). It is one of the most emotionally and musically nuanced pop songs ever recorded.

Morrison wrote Ballerina a powerful tale of yearning, in 1966 about the same time he first met his future wife, Janet. This tale of longing makes people cry.

Slim Slow Slider is a tragic song about watching a young girl die. The song ends abruptly with the words, “Every time I see you, I just don’t know what to do.” It has been said to be about a junkie but Morrison only has said that it’s about someone “who is caught up in a big city like London or maybe is on dope, I’m not sure.”

The album caught the attention of Sean O’Hagan, a brilliant music reviewer with The Observer, who praised its “vaulting ambition. It is neither folk nor jazz nor blues, though there are traces of all three in the music and in Morrison’s raw and emotionally charged singing”.

Greil Marcus, Rolling Stone’s first rock critic (who had reviewed the album very favorably in 1969) and a noted music author claims Martin Scorsese told him that the first half of his movie Taxi Driver was based on Astral Weeks. In an NPR review, Marcus said he has listened to Astral Weeks record more than any other album.

“You can hear these moments of invention and gasping for air, and you reach your hand and close your fist and when you open your fist there’s a butterfly in it. There was really something there, but you couldn’t have seen it. You couldn’t have known.”

He asserts that Astral Weeks served as a touchstone – “a common language” that reached across generations.

“I was so shocked when I was teaching a seminar at Princeton just a couple of years ago, and out of 16 students, four of them said their favorite album was Astral Weeks. Now, how did it enter their lives? We’re talking about an album that was recorded well before they were born, and yet it spoke to them. They understood its language as soon as they heard it.”

Elvis Costello: “Astral Weeks is still the most adventurous record made in the rock medium, and there hasn’t been a record with that amount of daring made since.”

Johnny Depp, in a Rolling Stone interview in 2008, recalled how when he was a preteen his older brother (by ten years) tired of Johnny’s favorite music of the time said, “‘Try this.’ And he put on Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks. And it stirred me. I’d never heard anything like it.”

Stevie Van Zandt (Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band): “Astral Weeks was like a religion to us.”

Alan Light of CNN/Time magazine: “Astral Weeks didn’t reach the charts, but its mystic poetry, spacious grooves, and romantic incantations still resonate in ways no other music can.”

Glen Hansard of The Frames: “It made me realize that so much of what makes music great is courage, and up to that, what I thought made music great was practice and study…This album says there’s more to life than you thought. Life can be lived more deeply, with a greater sense of fear and horror and desire than you ever imagined.”

People who got the album under their skin (including, obviously, me) never let it go. As a result, the album born of desperation, death, and pain now regularly outpolls its modest sales. Mojo, 1995, declared Astral Weeks the second-best album ever made. London Times 1993, called it the third, as did Time Magazine, 1996. MTV, 1997, said it was the ninth greatest. Rolling Stone, 2003, gave it number 19.

In November 2008, Van Morrison performed the entire Astral Weeks album live at the Hollywood Bowl. The concert featured guitarist Jay Berliner from the original album. A DVD of the concert was reportedly withdrawn at Morrison’s insistence but it is now available and easily streamed.

Many people have never encountered Astral Weeks. If you are one of them, stop the madness and stream it now on Spotify, YouTube, or Apple Music.